The Cohoke Fishing Club is a forty-seven member private sports club located in the heart of central Virginia. Over the years, their fishery has produced a significant number of largemouth bass weighing between 5 and 10 pounds, but success has been inconsistent. Some years, members catch over 50 trophy bass, other years as few as three. Members, along with state biologists, could not figure out how to stabilize the fishery and achieve consistent results. The pond had potential, but was not managed to produce large numbers of big bass.

Rich in history, the club's property was deeded to a man named William Caliborne in 1652 by the Queen of England as payment for passage of one hundred people from England to America. Caliborne received 50 acres of land per person he sponsored, totaling 5,000 acres. In 1678 Caliborne's son, Thomas, had an 85-acre millpond built to run a gristmill for grinding wheat and corn. In 1900, Cohoke Fishing Club was formed and purchased the pond along with the mill. The mill operated until 1960 when, after nearly 300 years, it was taken down. Fast forward to 2009 and this fishery, which has had its share of both high and low years, was at a low point. Bass caught were poor quality, numbers of big bass caught was down, and the pond was infested with hydrilla, a highly invasive exotic aquatic plant. At this point, the club decided to work with a professional fisheries management company to improve its bass population.

After meeting with a concerned club member and learning about the pond, it was apparent this troubled waterbody had some great qualities. Rich with life and bursting with fresh water much of the year, its 26,000 acres of undisturbed watershed provided an annual average flow rate of 8.66 cubic feet per second (CFS), or nearly 5.6 million gallons of water each day. Being a mill pond, it's shallow, averaging 4 feet. It has a long, narrow shape, providing roughly four miles of wooded shoreline to serve as great natural cover for a variety of fish species and sizes. This abundance of water teamed with natural cover creates great habitat for warm water fish species.

Unlike most managed fisheries we encounter, this club has kept incredible fishing records. For decades they have been recording variables such as quantity and length of each species caught as well as the date, number of hours fished and who was fishing. Additionally, all bass larger than 5 pounds had both length and weight recorded. Having this data in an organized form provided insight into the fishery's history along with some understanding of why the fishery produced inconsistent numbers of big bass over the years.

Following a meeting between club members and professional fisheries biologists, a review of the extensive dataset, and some electrofishing, it was clear the current fishery was far from producing consistent numbers of big bass the club would prefer to catch. Similar to how a car engine must fire on all cylinders to run properly, successful fisheries cannot produce great results year after year unless they are also firing on all cylinders. If even one variable is out of balance it can prevent a fishery from reaching its full potential.

The mission? Figure out what elements needed attention, and give them what they needed.

The most glaring issue was the hydrilla infestation. The upper end of the pond was a 50-acre field of plush, topped-out hydrilla. Shallow water was literally being strangled, and an aggressive approach was needed to regain control. Since it was fall, 2009 when the initial assessment of the fishery took place, it was decided to hold off until spring before implementing control measures. Based on budget and site conditions, the best long-term control method available was to stock 750 ten to twelve inch white amur, grass carp. In addition to these fish, a 10-acre channel in the upper half of the pond was treated with approved herbicides to ensure angler access to the entire pond that summer. With this approach, hydrilla was 100 percent controlled the first growing season, leaving the fishery in a transition phase where it needed to regain balance due to the abrupt change in habitat.

The initial electrofishing study indicated gizzard shad made up the majority of the forage fish base. Bluegill and other sunfish species were present, but low in population relative to the shad, due in part to decades of anglers harvesting all bluegill and releasing all bass. This past management strategy played a significant role in the shad's dominant position. Making changes to the bluegill population was implemented by eliminating their harvest and stocking 6,000 adults to help the population rebuild itself through recruitment. Managing fish species with a low budget required the club to focus on habitat and predator-to-prey ratios. The theory behind this method encourages fish species best suited for the habitat to thrive, allowing the fishery to become self-sustaining and producing an abundant forage base capable of supporting the club's desired bass fishery.

Also identified in both the initial electrofishing study and the past creel data was that the pond had far too many intermediate-size bass. Information provided by the club indicated 78 percent of bass caught were less than 15 inches long, and this overpopulation was playing a large role in poor bass growth. When managing fisheries with a limited budget, one of the most impactful ways to improve size and quality of fish caught is to implement proper creel limits based on goals. To improve bass fishing, the club needed to start harvesting as many intermediate-size bass as possible.

After closely examining the pond, we learned most of the fish cover was along the shore in the form of fallen trees. Fortunately for bass, the narrow width of the pond provided sufficient access to the gizzard shad population. The shoreline provided approximately 90 percent of the needed cover. All that was missing were two dozen pockets of structure spread in open-water locations to provide bass an even easier time ambushing shad.

Water quality is another critical variable that can affect a fishery's potential. Even with the high rate of flow the pond was fertile and maintained a plankton bloom for much of the growing season. During summer months the ponds' watershed tended to dry up, resulting in little or no water flow for a couple months. This momentary stagnant period allowed plankton populations to flourish. To aid in the ponds productivity in 2010, the management approach was modified and a few hundred pounds of quick-dissolve fertilizer was added during summer months.

With the fishery now getting an annual nudge with fertilizer, water quality could diminish due to increased primary productivity. A dissolved oxygen profile of the water column was taken twice each summer for several years. The results of the data showed adequate water quality, but dissolved oxygen levels in the bottom two feet were depleted mid-summer. This information was helpful and identified fisheries productivity and water quality limits were being pushed about a far as safely possible.

Cohoke Fishing Club, like many fishing clubs, had to overcome several internal struggles prior to achieving the desired results. One of the biggest challenges was educating members: do not catch and release intermediate-size bass. No matter how frustrated about size and health of the pond's bass, it was very difficult to get anglers on board with doing the opposite of what their Dads and elders had taught them. Upon gaining a full understanding of the fishery and the club's stance on keeping fish, it was clear this inherited resistance to harvesting bass was the primary hurdle preventing the pond from producing more consistent, high quality fishing. Regardless whether other cylinders within this fishery's motor were firing properly, the negative impact of failing to complete this step of the management strategy was strong enough to keep the fishery from reaching its potential.

Once we identified the variables limiting bass growth, a strategy was implemented to address each of the limiting factors. As for harvesting bass, the majority of members were not willing to buy into the approach of removing bass less than 15 inches. Some admitted they were still fearful that catch rates would drop off significantly, while others simply did not think harvesting bass was a good strategy and believed it would hurt the fishery. Due to strong reservations at the time, the club implemented more

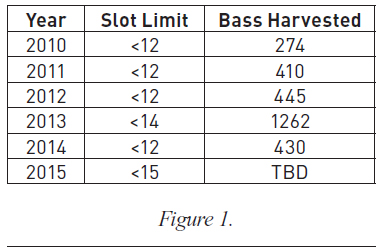

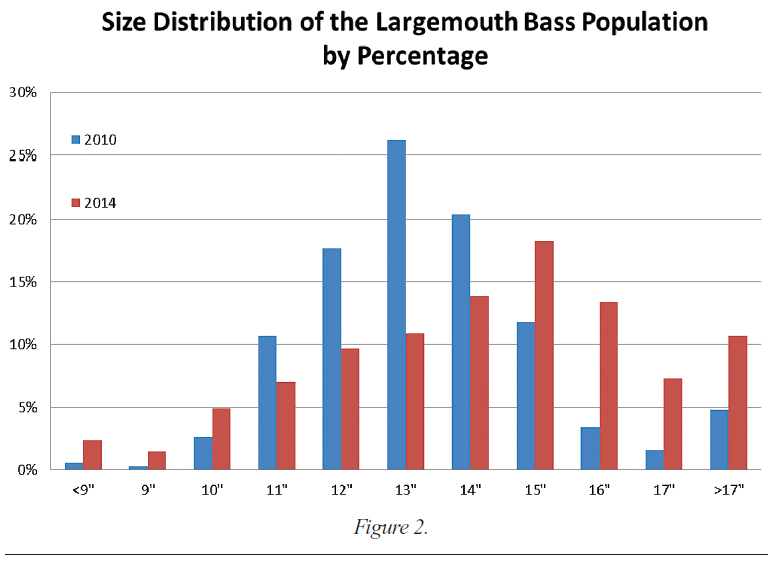

Now, in 2015, it has been 5 years since the strategy was set in motion. Over that time the management tasks have been carried out annually. Although not all of the members of the club would conform to harvest recommendations, they did make strides in the right direction. One great strategy they adopted was to harvest all other predators present in the pond, including black crappie, chain pickerel and white perch. Figure 1 shows the creel limits for largemouth bass the club followed. These revised creel limits were not ideal, but they were significant enough to make a big impact. In line with the concern of some anglers, catch rates gradually decreased from 1.25 bass per hour down to 0.96 fish per hour over 5 years, but the quality of the bass has increased significantly, as seen in Figure 2. Currently 50 percent of the bass caught in the pond are greater than 15 inches. In 2010, prior to actively harvesting bass, only 22 percent were greater than 15 inches. The 20 percent lower catch rate in exchange for a positive shift in quality and size of fish has obtained enough support from the club's members to start harvesting all bass less than 15 inches beginning this year.

The extensive historical fishing data from this pond illustrates it has potential for greatness. In order for the club to continue with its recent success, members need to stay focused on each of the following variables that impact bass growth: predator-to-prey ratios, water quality, plankton production, fish cover, otters, record keeping and harvesting. Keeping a fishery firing on all cylinders is what sets successful fisheries apart from ones that simply do not produce. For some, the biggest hurdle is getting owners and anglers to buy in on the management strategy and understand they play a critical role in their own success. If fishermen do not follow through with management tasks required, then the system is not firing on all cylinders and the fishery will not meet its potential. Are you willing to do what it takes to make your fishery thrive?

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine