Heavy rain has a way of devastating communities and properties across this great country. It seems common to hear of places that receive 6-8 inches of rain within a 48- hour period. During these flooding rain events, ponds and lakes must receive a large increase of incoming water within a short period of time, and release excess water in an orderly fashion. When this occurs, fish movement in and out of ponds can be a real concern.

During a rainstorm, pond flooding can occur in one of two ways: either it's inundated with water from upstream or back water from downstream. Flooding from upstream occurs when a large volume of water falls upstream in the watershed, resulting in a surge of water entering the pond's inlet. This can overwhelm the primary outlet structure, (by design), resulting in a large amount of water leaving the pond over the emergency spillway (by design). Additionally, this type of flooding involves swift-moving water at the pond's inflow and outflow, and oftentimes is a short-lived incident, measured in hours rather than days. Downstream flooding, on the other hand, is when water levels downstream of the pond rise high enough that water breaches the pond's embankment. This type of flooding oftentimes involves slow-moving water and can last days before downstream water levels recede. This past September, several ponds that we manage in the Mid-Atlantic region fell victim to flash flooding from two different hurricanes, three weeks apart, and were inundated by water flowing from upstream. One of these ponds was a Virginia based, 4-acre pond built in 2015. The pond has a 100-acre wooded watershed with a flattish gradient. The fishery was well-established and the client was nearing his goal of owning a trophy Largemouth bass fishery.

One rainy afternoon in late September, I received a troubling phone call breaking the news that two days prior, a rain event flooded his pond, and he was now looking to schedule an electrofishing study to assess his losses.

During our monthly onsite consulting throughout the 2018 growing season, we observed the pond thriving with golden shiners, fathead minnows, and threadfin shad. The forage populations pushed the limit on the pond's carrying capacity with hundreds of forage fish appearing everywhere you looked across the surface. The forage base consumed 18 pounds offish feed daily throughout the summer. Then, just two days after the rain event, the client described how no forage fish could be observed anywhere, and there was no feeding activity.

To say the client was sick to his stomach was an understatement. He proceeded to share the details of what lead to his grim observations of the situation. He described how he was hit with nine inches of rain within 36 hours, and how the watershed was overwhelmed. To make matters worse, a wet-weather creek that parallels his property could not handle the rainwater and jumped its bank a few hundred yards above his pond. His watershed is comparatively flat, and this creek that normally bypasses his pond became significantly overwhelmed with water, creating a new path through the woods before pouring into his pond. The sheer volume of water entering his watershed overwhelmed the outflow and the pond began to swell. Fifty percent of the pond's perimeter is a man-made embankment, and the emergency spillway was an elongated low spot located halfway between the pond inlet and outlet. The relentless waterflow resulted in the 200-foot-wide low spot to be inundated with thirty-six inches of flowing water. For a period of 24 hours, the pond turned into a moving waterbody.

That's enough volume, width, and depth to entice movement of fish.

Based on the lack of visible life in the pond, and teamed with no forage fish feeding, the client had braced himself for a total loss. Could all of his fish make an exodus with such high flow rates and such a significant volume of water inundating his pond? Within a couple of days, we were on site to sample the fishery with an electrofishing boat. Several hours later, we determined that nearly all of the golden shiners and threadfin shad had packed their bags and left the pond, and that a majority of the fathead minnows had left. During the sampling, it appeared that few fish—if any—had entered the pond from upstream during the flood event.

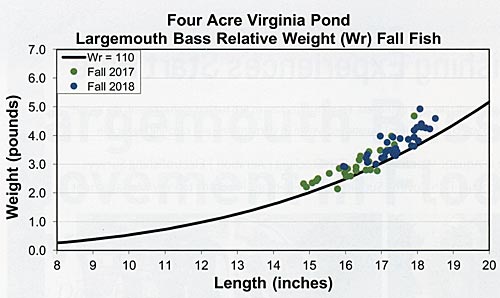

The pond's Largemouth bass population was all-females, stocked 18 months prior. During the sampling, 31 of the females were recaptured, with a Catch per Unit Effort (CPUE) of 47 fish per hour. The bass population had an average relative weight (Wr) of 126. At first glance, it seemed the bass population was in good shape given the number of bass collected. To help confirm our opinion, we reviewed our sampling data from the fall prior, which indicated that 26 bass were collected with a CPUE of 30. Comparing the two data sets helped indicate that the bass did not leave. To help further support our position, scientific literature indicates the bass population should have naturally depleted by as much as 20% in the 12 months between the two sampling events. Since we collected more bass in the second year, and our CPUE was higher, and because a CPUE of 47 is good given the limited number of bass in the system, we are comfortable that most of the bass stayed home and did not leave the system, even though approximately 2,000 pounds of baitfish left overnight.

Following the sampling, the client was able to sleep a little easier at night, even though it still hurt to lose such a large amount of forage. Bass growth will suffer noticeably due to the loss of forage fish, and as a result, the bass will not reach their full growth potential. To help compensate for some of the lost forage and get the bass headed back on track, the client restocked 500 pounds of golden shiners.

Another pond we manage also flooded last fall. The 1.6-acre pond is located in North Carolina, and it too flooded due to a large amount of water falling upstream in the watershed, resulting in a significant amount of water leaving the pond over the emergency spillway. The pond was being managed for trophy Largemouth bass, and all of the bass were PIT tagged. Following the flooding event, the pond was electrofished, and the data set, teamed with observations, indicated that nearly all of the golden shiners and threadfin shad had left the system. Few fish if any entered the pond from upstream, and the data indicated that the Largemouth bass stayed.

Although the data sets from these two ponds mirrored each other, I have heard many stories of ponds in the south that experienced far different outcomes. Many of the contrasting experiences shared with me, where the Largemouth bass left the system, involved ponds that flooded due to downstream water rising high enough to breach the pond's embankment, rather than rapid water flow over the emergency spillway. Since these flooding events involve slow moving water, the Largemouth bass population is more comfortable traveling outside of the pond's natural footprint, resulting in more bass leaving during these types of flooding events. Additionally, flood events of this nature seem to result in a large number of trash fish entering the system, such as common carp and longnose gar. This is because the natural home range of trash fish is typically downstream of man-made ponds, in rivers and lakes.

Even though we have a limited number of high-quality pre- and post-flooding data sets related to small impoundments, our findings that Largemouth bass are less likely to leave a pond when swift-moving water is flowing through it makes sense, since Largemouth bass prefer calm water. There are certainly exceptions to this. Paul Dorsett, an experienced biologist on our staff in Texas, has witnessed a significant number of Largemouth bass leaving a two-acre pond during an upstream flooding event. Why bass left that pond is unknown, but it is possible it had to do with the time of year, or possibly stressful water chemistry coming in from upstream.

Although both upstream and downstream flooding events can be devastating, our data suggests that you can minimize the damage to your Largemouth bass fishery during flooding if you design your pond in a way that ensures that downstream water is never able to breach the pond's embankment. Although this sounds like common sense, building ponds can be expensive, and making the decision to increase the height of a levee can cost a lot of money. Before you invest a great deal of money into your fishery, consider all of the risks of failure, including flooding from upstream and downstream.