A dull-orange, waxing crescent moon hung low on the horizon, almost too big to be in the July summer sky, as it descends tonight. The air is warm and humid but there is a breeze gently blowing over the lake, lapping at the chines of the aluminum boat hull, making a gentle slap and slurp sound that is almost hypnotic. The big dipper is also low in the night sky, and as I sit in the darkness, a screech owl wails far off, muffled by distance. The serenity is not diminished by the white LED glow of the headlamps of four students swarming from the shore to the boat in which I sit, as they diligently work to load gear for the electrofishing survey we're about to start. I sit there watching and think to myself, "How many times has this night-time electro-fishing scene played out?"

Dozens?

Certainly not hundreds? Yes, hundreds. Mark. Mark. Hey Mark! The student crew leader Steve Stowell, whose project we are here for, breaks my trance—and waxing nostalgia. He says, "Are you ready?" I snap out of it, answering, "Sure let's go!" The generator whirls to life as the tranquility of the night is broken into 15 minute noisy electrofishing runs. Yellow light floods the front of the boat, splashes and the sounds of students whooping with encouragement are heard as they net swirls of stunned fish.

Why were we there? A return to Moe Pond. Located about a mile outside of historic Cooperstown, New York, Moe Pond is a 38.5-acre largemouth bass playground with shallow water, downed trees, and plentiful elodea. Moe Pond is a biological field station site, access is controlled, and it is off limits to most fishing. This makes it a unique study area—and plying these waters with e-juice has formed some of my opinions on how bass work in small lakes.

The fish chronology of the pond is interesting. Here is the long story made short. Twenty years ago there were only golden shiners and bullheads in the lake. The shallow water was green with planktonic algae that grew in the absence of large zooplankton. The shiners kept the grazing zooplankton knocked down. Then, in an unauthorized introduction, largemouth and smallmouth bass were added by some bucket biologist. The bass thrived. During the early bass years, almost equal numbers of smallmouth and largemouth were observed. Golden shiners diminished as the bass population increased. The water cleared as large zooplankton returned. Ten years ago, on a night similar to the one described, I electrofished Moe Pond with the same boat. Smallmouth bass and golden shiners were gone. Largemouth bass were so abundant they were stunting and bullheads were scarce. The pond was green again as juvenile largemouth were now filling the role of dominant plankti- vore. A pond once dominated by golden shiners and brown bullhead was taken over by largemouth bass. The pond was bass on bass, and they were all in that typical, telltale, farm pond, bottleneck 8-10" size. Fast forward to tonight—10 years later, we were here to do an update. Was the pond still bass on bass? Hold on....

More specifically, our group was back to Moe Pond to do a population estimate. We were interested in how many bass were in the pond. Because it was such a warm night, we shocked 10 test fish to see how they would respond to the electricity and observe how they would recover in the live well after receiving an identifying fin clip. After observing the fish recover well, we decided to start the study. The goal of the evening was to shock the entire shoreline of the pond, netting all fish. Each fish was measured and received a partial pelvic fin clip so they could be identified later for the mark and recapture population estimate. All fish were released back into the pond.

We were using the Petersen mark and recapture method. This method is used for a single mark and recapture. Here's how we did it. On the first night we caught and clipped a total of 450 largemouth bass. Those marked bass were re-leased back into the pond. We gave the fish a week to recover from the electrofishing and marking. The group returned after the week and electrofished the pond again in exactly the same way, duplicating our first effort. The second night we caught 356 fish of which 86 were recaptured (they were marked with fin clips). A simple proportion, cross multiply and divide, gives us an initial bass population of 1863 largemouth in the pond. Why do we care about population estimates?

No one likes an overcrowded place. Overcrowded bass are usually stunted bass because there is less available forage. At a young age, fish are primarily omnivores, foraging on small invertebrates and zooplankton. As the fish grows, it transitions from insects to small fish and so on. What if there are no forage fish for these predacious bass to eat? The fish stunt, remaining small.

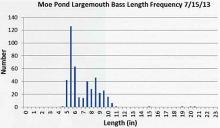

The chart shows length frequency of the 450 largemouth bass caught at Moe pond in one trip around the pond during 2900 seconds (.8 hours) of fishing or a catch rate of 560 bass per hour. WOW! And...drum roll please...all but 4 of these 450 bass were 5-11". Seriously? Yep. This is what happens when a pond is overcrowded with fish competing for the same forage. BUT—take a look at those 4 outliers. One fish at 15", one at 19" (4.5 pounds), one 20" (5.5 pounds) and one 21" (6 pound) monster! For New York state, these are HUGE bass, folks. As a bass angler myself, those fish are absolute chunk Moe Pond monsters. They will bend your rod and give you a rough thumb, every bass fisherman's dream.

So, obviously these three largest fish have found adequate forage to survive and dominate within the pond. They are eating whatever they want in this pond—especially other bass. Note the photo of us pulling a 12" bullhead out of the 20" bass' mouth. These bass and this situation are very interesting to me. It brings me to the question: Why aren't there more monster six pounders in a pond like this? Why are they only .5% of the population? This pond is closed to fishing and is patrolled. Very few (if any) are removed by fishing. So that's not the reason. My answer is the same as always. Most of the resources are taken up by the 436 bass in the 5-11" range. But, a few bass, a few SUPER bass, less than 1% of the population, are able to grow fast enough to get an advantage over their kin. Then they can cannibalize their brothers and sisters and eat fish, while the small fish are stuck eating plankton. Just look at the bellies on these bass. They are in excellent condition with unlimited food that is absolutely everywhere.

So if this were my lake to manage, what to do?

Release those monster bass and let them grow. Then cull, cull, cull, the bass in that 6-10" slot. How many? Probably as many as I could catch. I learned something on this survey. A bass on bass pond (with a few bullheads) can produce fish in the 6-pound class in New York. That's progress. When I see a New York ten pound bass, and someday I really do hope to, well then I'll eat my hat.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine