What is competition? The word may conjure up images of your favorite sporting event or an episode of Survivor on television. Whether it's the Indianapolis Colts versus the New England Patriots or a few starved islanders jockeying for immunity from elimination, competition can be defined as a contest for a limited resource, perhaps a trophy or a million-dollar prize. Competition happens in the aquatic world as well. The phrase "survival of the fittest" is a familiar term to many. Fish may vie with others of their own species (termed interspecific competition) or with another species (termed intraspecific competition) for food supplies, living space, or other resources that may be in short supply. The problem may be exacerbated when new species are introduced into an already-established and stable community. A new predator with a diet similar to one or two native species can induce new competitive interactions, which may have negative effects on growth, reproduction, and abundance of the native organisms.

Such was thought to be the case in South Dakota. The walleye is the state fish, and quality fisheries can be found from border to border in natural lakes, small impoundments, and the Missouri River and its reservoirs. Beginning in the early 1980s, the South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks (SDGFP) wanted to provide new and diverse fishing opportunities and began stocking smallmouth bass into the Missouri River reservoirs and a few natural lakes in eastern South Dakota. The smallmouth bass populations were easily established with minimal stocking efforts, and sizes of these fish rival Lake Erie trophy fisheries! However, walleye anglers began to catch 4-5 smallmouth bass for every walleye hooked and believed that the sizes of walleye now being harvested were smaller than before the introduction of the bass. Perhaps the smallmouth bass were competing with the walleye for limited prey?

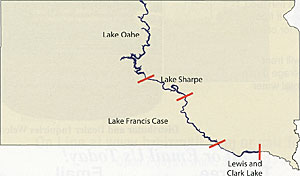

In 2006 and 2007, SDGFP and South Dakota State University (SDSU) worked together to study the diets of walleye and smallmouth bass in Lake Sharpe, one of the Missouri River reservoirs (Figure 1). Every month, from May through October, crews collected various sizes of walleye and smallmouth bass and sifted through stomach contents to find out what these two species were eating. Diets of the two species were similar during both years, particularly during the months of July-September when gizzard shad (a favored prey species for many predatory fishes) became available for consumption. However, these results only indicated the potential for competition. Recall from our earlier definition that competition can only occur when a resource is limited. Young gizzard shad are quite abundant in Lake Sharpe from mid-summer through fall. Almost every walleye and smallmouth bass stomach we examined was chock full of gizzard shad, and other predators such as white bass and saugers were also feasting on shad during the Summer. So, while the diet work from Lake Sharpe provided a nice picture of what walleye and smallmouth bass were consuming, it still didn't answer the question of whether these two species were competing with each other for prey. But all was not lost-experiments could be conducted so that prey conditions could be manipulated to examine competition between the two predators.

Scientists who study competition for food actually design experiments in such a way to find out who the better competitor may be under conditions of scarce prey and to understand how the better competitor is able to obtain food before the weaker species. Growth of fish is typically used to identify the better competitor, with the idea that "winner" will maintain or increase its length and weight and the "loser" will lose weight. Such growth experiments can be designed in such a way as to tease out intraspecific competition (for example, walleye versus walleye) from interspecific competition (walleye versus smallmouth bass).

During summer 2007, we installed nine 475-gallon tanks at the Wet Lab at SDSU (Figure 2). Each tank was assigned one of three treatments: six walleye alone (intraspecific competition), six smallmouth bass alone (intraspecific competition), and three walleye and three bass together (interspecific competition). Before the experiments began, we weighed and measured each fish and gave them a unique fin clip to identify them when the experiments were over. Every three days, we fed each of the tanks a very limited ration of fathead minnows. After a few weeks, we found that when walleye were alone or when smallmouth bass were alone, all of our fish maintained or gained a small amount of weight. However, when walleye and smallmouth bass were together in a tank, the smallmouth gained weight while the walleye lost weight (Figure 3). We repeated these experiments for age-1 walleye and smallmouth bass and found the same result (Figure 3). So, we concluded that smallmouth bass were better competitors than walleye when prey availability was very scarce. What we still didn't know was the mechanism for competition, or how the smallmouth bass were better at getting that prey.

Different types of competition exists. In one case, the better competitor uses the resource before the weaker competitor can; this is called exploitation competition. In another case, the better competitor prevents the other competitor from using the resource, perhaps by scaring or chasing it away; this is called interference competition. To find out which type of competition is occurring, fish must be observed. We were able to do just that given the generous contribution from the Jesse W. West Research Endowment that is intimately tied to Pond Boss (see Issue XV, Number 5, pages 22-23 in 2007 for more information on the endowment).

Last summer, we purchased four 180-gallon observation tanks (Figure 4). Because competition is often more evident in younger fish, we observed age-1 walleye and smallmouth bass in our tanks. We conducted five trials of three treatments: two walleye together, two smallmouth bass together, and one walleye and smallmouth bass together. We gave our predators ten fathead minnows, watched them feed for 30 minutes, and recorded the attack rate (the number of times the predator nipped, bit, or gulped a minnow) and capture efficiency (if the predator went after a minnow, did they consume it?).

We found that attack rate varied widely across all treatments, but it appears that walleye attack prey more often in the presence of smallmouth than in the presence of another walleye (Figure 5). Smallmouth bass, on the other hand, may not go after prey as often when walleye are around compared to when only another bass is present. However, walleye were still efficient at capturing prey when smallmouth bass were in the tank with them, but smallmouth bass efficiency was slightly diminished in the presence of walleye (Figure 6).

Another phenomenon we observed but did not quantify was that smallmouth bass would often display aggressive behaviors toward walleye in their tank. The bass would chase, bite, or "wiggle" at the walleye, possibly saying to them, "Back off, this is my food."

Overall, between the field work on Lake Sharpe and the experiments at SDSU, we've learned much about competition between walleye and smallmouth bass. It appears that subjected to limited prey resources that smallmouth bass can best walleye through their aggressive nature. However, we did have to limit prey to very low abundances to actually observe competition. In the natural world, these types of conditions don't often exist. Instead, abundant and diverse types of prey may be available, and predators can alter diets to adapt to these conditions. For example, crayfish are plentiful in some natural lakes in eastern South Dakota, and smallmouth bass take advantage of this while walleye might stick to a diet of yellow perch.

There is still much to be learned about how walleye and smallmouth bass interact with each other, and how other factors such as light level or prey diversity may affect competition. More experiments are planned for this summer, and thanks to the Jesse West endowment, we can continue to learn more about competition and feeding habits of these and other fishes.

Melissa Wuellner is a Ph.D. student and Dave Willis is the Department Head in the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences at South Dakota State University.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine