In the last issue, I described one of our research lakes and the process that led us to work on habitat. This 100-acre lake in Texas was suffering from the same symptoms of many ponds and reservoirs in the United States. They are old and have lost much of the structure needed to sustain healthy bass populations. Last issue, I left you with our conclusion we needed to add habitat and promised to tell the story and science of figuring out how much habitat to add to the lake.

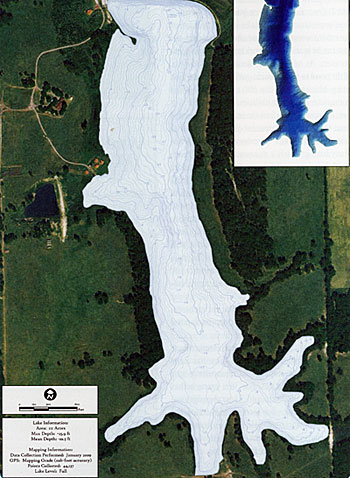

We started by tackling the problem from the same place that most managers and pond owners would logically start: Where? We looked at the lake bathymetry map to find highly attractive areas to add habitat: points, transitions, steep drop-offs, the types of spots that look fishy. We also had the benefit of hundreds of bass telemetry locations so we could verify what parts of the lake bass used most frequently. For 18 months, a Ph.D. student tracked bass movements in this lake via radio tags. The next question was what to put in these locations. Here is an area where science and private sector innovation helped us. There is a wealth of scientific literature, manuals, and handbooks, as well as a great collection of ideas archived in the Pond Boss Forum. We knew we needed complex structure, the landowner wanted a permanent solution, and longtime Pond Boss contributor Eric West provided the great idea that we needed to think of the vertical dimension so that bass could move up and down in the water column. We took these ideas and worked with one of the new habitat companies, Moss- back, to design a habitat treatment that was later named a Fish City. One Fish City combines 15 habitat structures. The premise behind the Fish City was to provide prey fish a safe passageway from shallow areas (two lay down structures) to a deeper water inner sanctuary (three high-density structures) that is surrounded by structural habitat for adult bass, including both shallow water (six low-density, short structures) and deep water (low-density, tall structures) elements. The overall footprint of a Fish City is approximately 75ft by 75ft (shoreline length x distance from shore). It covers water depths from 3-15ft.

We were excited to deploy the Fish Cities. We had a great habitat design and knew where to put it. Then we started thinking again about the science, and ran face first into the same debate that has plagued habitat studies for decades: "Attraction vs. Production." We have an abundance of studies showing that many fishes, including largemouth bass, are attracted to structure, but the question, "does adding habitat actually increase production of largemouth bass?" has not been answered. Here is the way to think about it. If you add a brush pile to your largemouth bass/bluegill pond, you will certainly notice fish are using the new habitat. In this case, you have taken existing fish and merely concentrated them in one area. If you add 10 brush piles, you are concentrating fish into 10 areas, but did you actually increase the production of largemouth bass? In other words, did 10 brush piles result in 10 more bass in the lake, or bass 10 times bigger than before, or 10 times more reproduction, or 1/10 of the previous mortality rate? To get more complicated, production typically means increasing the base of the food web, or putting more groceries on the table for the bass. The new brush pile supports increased production of algae, bugs, and small fishes that translates into either more bass or bigger bass.

So, how do we separate production from attraction? There are several great studies that evaluated the effects of habitat additions into lakes and reservoirs. Most of these studies collected data on the fish population before and after the habitat addition. Some of these studies documented a change in the fish population, but they were careful to state that they could not identify increased production. We needed our habitat addition to result in bigger bass, but the science had led us to a hurdle.

We pondered, discussed, read more papers, and finally realized that scientists had probably been asking the wrong question. Instead of "attraction vs. production", we changed the question to "how much habitat is needed to affect production?" Here is our logic. We can assume that fish are attracted to structure; this has been shown in many studies. We also can assume that when habitat quantity is above a certain threshold, then populations are enhanced (i.e., higher production). This idea came from the life cycle of a reservoir. Young reservoirs have enough habitat (brush, trees, etc.) to support healthy largemouth bass populations. As reservoirs age, habitat quantity decreases, resulting in declining bass populations. Therefore, if you reverse the aging process by adding habitat, at some point you will add enough habitat to support increased production, similar to a younger reservoir.

So, one of our new research questions going forward is "How much habitat do you need to add in order to increase production of largemouth bass, either in terms of abundance or growth?" This question has some caveats that should also be considered. First of all, even though loss of structural habitat is one of the top problems of aging reservoirs across the country, there are other symptoms, such as sedimentation and excessive nutrients, which should be considered (Miranda and Krogman 2015). Therefore, habitat addition will only be effective if water quality is also improved. Fortunately our study lake has great water quality, and does not suffer from excessive nutrients.

Another hypothesis

As we pondered our study lake, we realized that adding habitat might result in faster growth of largemouth bass simply by increasing the efficiency of the food web. Our study lake has very abundant bluegill, threadfin shad, and gizzard shad. That is, we have lots of productivity in our prey supply, but not enough of this production ends up in a largemouth bass. We realized that instead of increasing production of the entire food web, perhaps we could add enough habitat to re-plumb the food web. And that is the story for next time.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine