Introduction

A few years ago I was appointed chairman of the Pond Committee at the Loudoun County, Virginia, Chapter of the Izaak Walton League of America (LCC-IWLA). For those who don't know, the Izaak Walton League is one of the oldest conservation organizations in the USA. The mission of the league is to be defenders of soil, air, woods, waters, and wildlife. Our mission is conservation education. Our chapter has over eleven hundred members and provides various amenities including a beautiful five-acre fishing pond.

My committee's job was to make sure this pond would continue to be a great fishing resource for our members. I was quite excited about this appointment, but there was one problem, I knew nothing at all about ponds!

Seeking knowledge, I stumbled upon Pond Boss, immediately subscribed, and read every article in every issue I received. I was also fortunate that the local biologist at the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (DGIF) generously answered all of my phone calls.

From studying Pond Boss, I knew that the first order of business was to measure the pond's alkalinity and pH. It was clear that with an alkalinity of 20 parts per million (ppm) our pond needed to be limed. We wanted to push the alkalinity upwards to 40 ppm, hopefully higher than that. Our problem was to procure this lime in an area where farms had almost disappeared. Although our local stores sold lime, it was pelletized and not powdered. Fortunately, with help from the Loudoun County Extension Service, we discovered the Culpepper Farm Co-op in Marshall, Virginia, only thirty miles away. By the way, there are several different types of lime. We needed calcium carbonate, typically called aglime, often used as a soil amendment.

We calculated lime requirements based on having a three-acre pond (it was only later that we realized our pond was much larger). At one- ton-per-acre, we would need three tons. The cost was only about $25 per ton if we picked it up, but we had no way of transporting three tons of unbagged powdered lime. Our alternative was purchasing and transporting 120 fifty-pound bags. Although the cost was greater, about $450, we knew we could handle the logistics.

The next problem was evenly distributing and dissolving this lime into the pond. Fortunately for us, our Facilities Chairman, Ned, is a retired plumber and a mechanical genius. Using a jon boat, water pump, fifty gallon drum, and some PVC pipe, he designed the perfect machine. The fifty-gallon drum was secured to the jon boat. Pond water was pumped into the top of the drum. A volunteer dumped the bags of lime into the drum at the same time, and the resulting slurry poured into the pond via a pipe in the bottom of the drum.

Liming day arrived. In a driving rain our intrepid volunteers were able to distribute all three tons in about four hours. Within a week, our alkalinity had risen to about 100 ppm and has stayed that way for over a year.

Fertilization

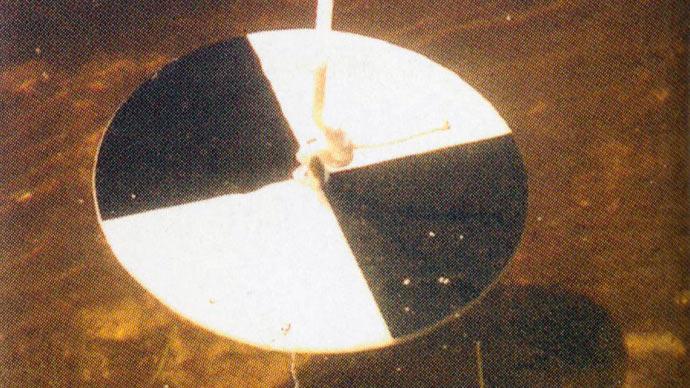

Generally, each spring our pond emerges from the winter with crystal clear water. Now is the time for fertilization. We are very conservative about this process placing only one 40-pound bag of nitrogen fertilizer into the pond at a time. Once the contents of the bag have dissolved we measure the phytoplankton bloom using a Secchi disk. If we can see more than two feet down, we add another bag.

We never pour the fertilizer into the pond. Rather we wrap the bag in plastic netting, cut slits into the bag and immerse it in about three feet of water. We mark its position with a buoy and a shore sign so anglers can avoid it. It takes about two weeks for the fertilizer to dissolve completely and then we remove the netting, bag, buoy, and sign.

Providing Structure

Our next job was to add structure to our pond. As it is over 50 years old, any trees originally left under the water are no longer there. Committee member, Dave, took the lead in this project. He discovered a YouTube video by Richard Shuford titled, "How to make a fish attractor." Gathering on lunkers over eighteen inches, we urged anglers to take a picture and return them to the pond.

But, posting slot limits was not enough. The key was educating the membership. At every monthly meeting we discussed the reasons behind our volunteers, we created about twenty structures, which were placed in the pond in groups, and then google-mapped for future reference. Our plan is to add to these reefs every year.

Slot Limits

Having read many articles in Pond Boss on how to grow bass big, we knew we needed slot limits. We decided that any bass less than twelve inches must be harvested, and bass from twelve to eighteen inches, released. Although we had no firm policy the slot limits and the need to harvest. There was some initial push back. We had to convince some members that catch-and-release was not an ethical issue but a management issue. To reinforce our message, we often walked the circumference of the pond discussing the slot limits with the fisherman. After about a year we were reasonably certain that every member who fished knew the rules.

Results

What have been the results of all of our work? Well, based on anecdotal evidence, anglers report that our bass are getting larger and fatter. This autumn one member caught a 28-inch Largemouth, the biggest ever recorded in our pond, and the best thing is, he threw it back! We named that fish "Old Izaak" and we are hoping she continues to thrive. Earlier this year, DGIF electrofished our pond. They were quite satisfied with the results. Their recommendation was to "continue to do whatever you are doing". That is exactly our plan.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine