What comes to mind when you hear that a pond or lake is stocked with all-female Largemouth bass? That pond is probably seeing exceptional growth rates among the bass? I bet they are catching huge fish? The management of that pond is difficult and is not something that I can do? When I hear that a pond is stocked with all-female bass, I think to myself, will that pond owner be patient and follow through to reach their goals?

The first few questions above are possible through stocking and managing for all-female Largemouth bass. As for the difficulty in managing, it is not so difficult. Managing an all-female bass pond involves basic pond management strategies we already know and utilize, with a few additions.

In my experience, one of the key components of creating and maintaining a trophy bass fishery based on having all-female Largemouth bass as the lone predator in the system is all about following through with the plan.

That's a big deal, and critically important. Sure, the stocking and management plans and periodic assessments to monitor population progress are important. But often, I have seen scenarios where the client did not follow through with the outlined plan. Or they grew tired of reduced catch rates associated with a trophy bass pond and changed strategies. The following is an example of how we helped stock and manage a pond with all-female bass, obtained great results, then had our involvement limited because of unforeseen issues with the long-term management of the entire property where the pond was located.

We had the privilege of working on an 8-acre lake in Northwest Florida that was renovated for an all-female bass project. Sections of the pond were modified and deepened to make them more interesting to the fish and to create better fishing. Structure was added to enhance forage fish cover and provide additional habitat for larger bass. These areas in particular were designed to attract bass to already-known areas to help improve catch rates for the bass', which are typically stocked at a lighter density. But more on that in a bit.

Once the pond had filled in the spring of 2011, bluegill, shellcracker (redear sunfish), golden shiners, and threadfin shad were stocked as the forage species for the bass. These fish were allowed to grow and reproduce without the influence of a predator until February of 2012. The pond was fertilized to improve its primary productivity, and there were two automatic feeders in use to provide a supplemental diet to the forage fish. In February 2012, 280 Tiger® bass (35 fish/acre) were stocked, which were 8-10-inch, all-female fish. These fish were about 10-11 months old at the time of stocking. By design, the forage fish were stocked heavy and the bass were stocked light to maximize bass growth rates.

Four months later, our first assessment of the population was completed. We observed that the group of bass had grown from a range of 8-10" at stocking to a range of 9-14", with most fish being in the 11-13" range. See Figure 1. The average relative weight of the bass was 95, with some individual fish reaching 110.

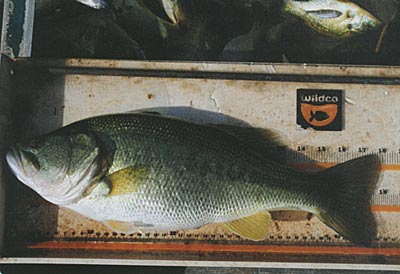

The next assessment was completed in January of 2013, 11 months after stocking the bass. At that time, we saw fish ranging from 14-18", with most in the 16-17" range. The average relative weight of these fish was 104, with some fish reaching 120-121. The largest fish in the sample had grown 3 lbs. in less than one year. See Figure 2.

Here is where the management of the pond went sideways. The property was put on the market for sale, and management of the lakes on the property was reduced to minimum inputs just to keep things going up to the sale of the property. This ended up being about a 3 to 4-year period of minimal management (maintaining aesthetics only), and no stocking inputs.

Had we been able to follow through with the plan, we would have monitored forage fish, watched bass growth rates, and prepared to cull the underperformers and add younger fish each year—to do what we could to mimic nature's recruitment the best we could. But our plans were changed.

Back to the bass numbers in the pond. Because a reduced number of bass were stocked into the pond, and they were all female fish, there should not have been bass reproduction in the pond. But as our original plan stated, we wanted to establish year classes of bass to fill in the gaps in the population distribution of sizes as the years progressed. This was for two main reasons. One is to create longevity or sustainability within the population so that as the original stock of bass dies out (of old age or from predators), there will be other fish moving up the sizes to replace them. The other reason is to maintain adequate catch rates for most anglers, since an all-female bass pond has lower numbers of fish and therefore can have lower catch rates, especially for novice anglers. These subsequent stockings of female bass did not occur since the new goal of the property was to sell, and the pond had the one original year class of bass in it that was no longer being tracked.

Fast forward to May of 2016. We were called in to reassess the pond to determine its status, even though the property had not yet sold. I was excited to see how the population had progressed and was particularly interested in how it fared without inputs to support the forage density. We observed a tight group of bass sizes ranging from 17 to 22 inches, with the most abundant size fish being 20 inches. The average relative weight was 97 and the maximum relative weight observed was 108. So, we were seeing trophy size bass in good to excellent condition after 4 years of having been stocked with bass. The forage density in 2016 was reduced from what we saw in earlier samples, but it was still good. Intermediate to small adult bluegill (3-7 inches) were the most abundant sizes in the bluegill population, and very few fish in smaller sizes. The threadfin shad exhibited decent density as we observed several different schools of them ranging in sizes from 3 to 5 inches.

One of the takeaways that we developed after seeing how the population had progressed over those few years where management had all but ceased was that even though the forage density in the pond had declined overall, there was still plenty of forage available to a limited number of bass, and present at sizes the bass could utilize to maintain excellent growth and condition. But what we saw was a reduced trajectory of the bass growth and overall condition even though the lengths of the bass continued to increase. In my opinion, one aspect of the bass population social interaction that wasn't happening, because of such a light density of bass in the pond, was competition. On some level, bass need that competition for food in order to stay aggressive in feeding and maintain those growth rates that we saw in the beginning of the project. Although we technically achieved our stated goal of producing trophy size bass, if we had been able to follow our original plan, and had stocked 2-3 more year classes of bass in the population, I believe we would have seen even stronger results with larger fish.

In conclusion, we have had the privilege of working on several all-female bass projects. Atop the list of the challenges to this way of managing a trophy bass population is being patient and following a plan to establish the population distribution of sizes through periodic stockings of bass year-classes. This will create the competition for food that the bass require to continue to feed aggressively and exhibit those growth rates and condition factors that we attribute to trophy bass populations. The reduced number of bass that are in a pond managed this way, and the reduced catch rate that can be associated with it, can be difficult to deal with over the long term for novice or average anglers. Some of our other pond owners managing their ponds in a similar way grew tired of the reduced catch rates and opted to return to a mixed sex population of bass by adding males to their ponds. Who knows what that population would have developed into had they stayed the course?

As for the all-female pond in Florida—it finally sold, and we are no longer involved with the management of it. But we look forward to working with the next client who is interested in managing one of their ponds as an all-female trophy bass pond. And we will take with us the lessons learned and adapt them to the needs of the pond owner.

Robby Mays is co-owner of American Sport Fish near Montgomery, Alabama. He's a fisheries biologist, in charge of pond management projects for the company.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine