"No other single factor affects the development and growth of fish as much as temperature" Piper, (1982). Piper (1982) further explains, "Metabolic rates of fish increase rapidly as temperatures go up."

I could not have said it better. These two sentences are why we care about temperature so much.

Temperature sets the stage for pretty much everything.

The temperature depends on the natural environment in which the pond occurs. The relationship between the intensity of incoming light and temperature is direct. The more direct sunlight a location receives, the warmer the air temperature, followed by the water temperature. Also, southern latitudes receive sunlight at a higher angle, making the sun's energy transfer to the ground and water more effective. This is the primary reason lower latitudes, or the south in the USA, are warmer than more northern (higher) latitudes. Simply put, the more intense, directly overhead sunlight a body of water gets, the warmer it will be.

Just like plants have hardiness zones, so do fish. A cactus from Texas will no more live in New York than a New York brook trout will live in a Texas pond. Optimal temperatures are 55-60°F for cold-water fish, 65-70°F for cool-water fish, 75-80°F for warm-water fish, and 85-90°F for tropical fish. Increased temperature causes increased metabolism in cold-blooded organisms like fish. Fish are aerobes that must consume oxygen. Fish consume oxygen at a higher rate in warmer water because they are metabolically more active and need to respire at a higher rate. As water warms, it holds less oxygen, but the fish need more because their metabolism increases.

Double whammy if evolution has not prepared a fish species to deal with warm conditions.

In addition to fish metabolism, temperature controls the density of water. Water is unusual because its solid, colder form (ice) floats on the liquid form. The solid ice is less dense than liquid water. Water is most dense at 39°F (4°C), and density decreases as it goes from 37°F (3°C) to 34°F (1°C) as a liquid, and then the density drops again at 32°F (0°) when ice forms. The density of ice is about 9% less than liquid water. That's why ponds inversely stratify in the winter. Ice is on top, and then under the ice is 1°C water, below that is 2 °C, below that is 3 °C water, then the densest water is at the bottom at 4 °C. In winter, the coldest, least dense water is at the top, and the warmest and most dense water is at the bottom. A pond is warmer at the bottom in the winter, and most fish are found on the bottom in winter.

In summer, the coldest, most dense water is also at the bottom of a pond. Pop quiz: In a northern pond, what is the water temperature at the bottom of a deep lake in the summer? If your answer was 4°C to 5°C (40's), you get an A+. In the south, expect bottom water to be as much as 20 degrees F colder than surface waters in the summer. The coldest water will be found at the bottom of a pond if it stratifies because colder bottom water is denser.

As previously mentioned, temperature (and pressure) also controls the amount of dissolved oxygen water can hold. Cold water holds more oxygen, and warm water holds less. There are two major pathways for oxygen to enter a pond—wind-assisted diffusion from the atmosphere and, to a lesser extent, photosynthetic activity from aquatic plants and algae. However, this second pathway is a bit deceiving because, at night, these photosynthetic organisms respire, consuming oxygen instead of producing it. The diffusion pathway is significantly reduced on warm, windless days in the summer. Warm water holds less oxygen than cold water, and undisturbed water provides the smallest possible surface area for diffusion.

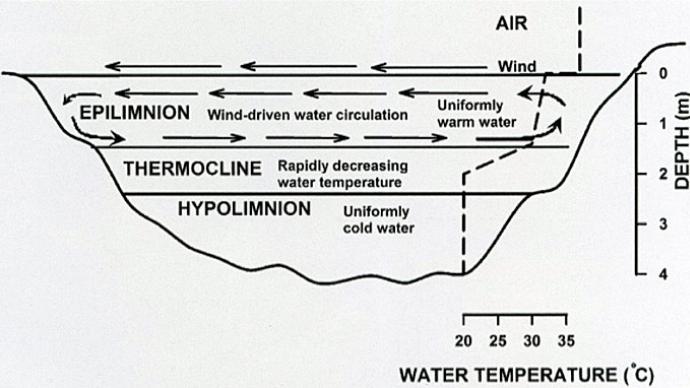

On top of this, the warm air and lack of wind can lead to "thermal stratification," where the pond has layers of different temperature water that tends not to mix. This means that any oxygen that makes it into solution cannot penetrate the cooler bottom waters.

The pond in this state will lose oxygen from the bottom up until prevailing conditions change. Algae-dominated systems tend to have a higher risk of experiencing a summer kill due to their short life cycle. They provide a constant stream of organic material falling to the bottom to be decomposed. In contrast, most rooted plants senesce (die) and enter dormancy in late fall when cooler waters and better mixing prevail.

Water depth plays a role in where and how the heat in water is distributed. Deeper waters are cooler than shallow water. The coldest water will be at the bottom of a deep pond in summer. "Is my pond cold enough for trout?" is a common question, but in most locations, the better question is, "Is my pond deep enough for trout?" In reality, most ponds are not cold enough for trout, even in the northern part of the U.S. Many ponds have a time during the year when they are cold enough for trout but also have a warm period when trout will die. The "incipient lethal temperature" is fancy speak for: "If conditions go above/below this temperature, fish will die."

The upper incipient lethal temperature for most trout is about 73 or 74°F. If a pond gets warmer than this, the trout will die. Water temperatures need to only be hot for one day in the lifetime of that fish to end it all.

Fish only die once.

Increased pond depth can compensate for a warmer pond location. However, most ponds are constructed less than 10 feet deep. To successfully grow trout in a New York pond, more than 1/3 of the volume is recommended to be deeper than 10'.

Altitude also plays a role in determining water temperature since high-altitude ponds are cooler than those at a lower altitude. In the Catskills area of New York, most trout are found in waters over 1200' in elevation. Why? Because that is where the water is cooler! Trout do not like water temperatures in the 70s, and most of the water is cold enough for trout in this region to occur above that elevation.

Conversely, most Largemouth bass do not grow well in higher-elevation ponds. In high-elevation, cold ponds, largemouth bass grow very slowly. A 16-18" bass in a New York pond at 2000' will likely be over ten years old.

Why? The high-elevation pond may never get warm enough for optimal bass growth. It's just too cold.

Temperature, along with wind and humidity, also play a role in the evaporation of water from a pond. During peak summer months, many ponds lose 6-7 inches of water a month, equating to almost a 1/4" of water loss from evaporation per day! In July, August, and September, our 1.25-acre pond may lose 18" of water if not supplemented by rain in a dry year. Deeper ponds with a smaller fetch (wind exposure) may have less of a problem. Is it located in an area with a hot, dry summer? Expect to lose a similar amount of water (and depth) in your pond.

In the lives of our ponds, temperature is the key to all.

Mark Cornwell is a professor of fisheries at the State University of New York in Cobleskill, NY. Based near the Catskill foothills, he feeds the brains of hungry fish students, offering plenty of applied science and hands-on opportunities beyond the classroom. Cornwell also works with select local landowners, collecting data and analyzing ponds, with students receiving the benefit. He also assists the college's aquaculture department.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine