Losing too many of the bass that grab your crankbait? Need to dial in the accuracy of your pitches, flips, and casts? Finesse lures don’t have the wiggle that they should? While the practice may help, these issues and others like them are often the result of mismatched lures, rods, reels, and lines.

Balanced outfits make everything easier: casting, fishing, catching, and landing. And the less you worry about and fight with your gear, the more you concentrate on uncovering patterns, working your lures, and catching bass.

But while the benefits are simple, assembling a balanced outfit takes thought. The process starts with the lure that you’re fishing. Identify its needs, and you can select the best rod, reel, and line that meet them.

Lures

All lures fall into two groups: horizontal presentations and vertical presentations. Some lures, such as lipless crankbaits, can be placed in either group, depending on how they’re fished. But each group requires a different outfit.

Lures that are fished horizontally are used in power fishing techniques. They include topwaters, spinnerbaits, bladed jigs, jerkbaits, and crankbaits. Most have scoops, blades, or bills that give the lure action, flash, or vibration during a steady retrieve. They generally require long casts that don’t always have to be accurate. Most are heavy, pull firmly, and have treble hooks.

Most, but not all, vertically presented lures are used for finesse tactics. They include soft-plastic lures, jigs, and jigging spoons. The rod tip is used to hop or drag them along the bottom, imparting action that they cannot create themselves. Most have a single hook, sometimes buried inside a soft-plastic lure, and move through the water with little resistance. Bites can be soft.

Rods

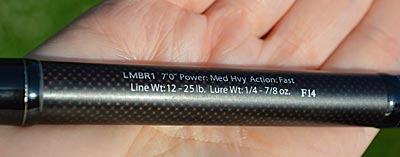

Once you know your lure’s needs, you can build the balance of your outfit. Its backbone is the rod, and choosing the best one for the task requires selecting the best mix of action and power.

Action describes a rod’s flex. It ranges from slow to fast. Crankbait rods, for example, have a slow action because they bend from tip to handle, creating a parabolic bend. Fast-action rods such as flipping sticks are at the other end of the spectrum. They only flex in the top one-third of their blank. Between them are various actions such as moderate-slow, moderate, and moderate fast. As their names imply, they flex differently but always less than slow actions and more than fast-action ones.

Slower action rods are best for lobbing lures great distances when pinpoint accuracy isn’t vital. They give bass time to engulf a lure because your hookset loads the rod and then moves the line and lure. That sponge-like quality also keeps bass hooked on trebles. With your force spread across so many points, you have to keep the line tight to keep them stuck. A slower action absorbs a bass’s moves that create slack. Fast-action rods provide casting accuracy and powerful backbones to set single hooks made from thicker diameter wire.

Power describes the load that a rod can carry. Light-power rods, for example, handle small lures and lines. As with action, rods increase in power to medium and then heavy, with some on either extreme earning superlatives such as ultra and extra. An extra-heavy rod, for example, is best at casting the biggest lures or pulling big bass from heavy cover with vertically presented lures.

A rod can fall anywhere on either spectrum. Big deep-diving crankbaits, for example, demand rods with a heavy power but slow action. But if you’re planning to fish a lightweight finesse baits, such as a split-shot rig, you’ll want a light power matched with a fast action's sensitivity and hook-setting power.

Don’t dismiss the material that a rod is made from when considering action. Rods made from fiberglass, for example, nearly always have slower actions than graphite rods. Many manufacturers blend the two, looking for the perfect combination of flex and sensitivity.

Nearly all of today’s bass-fishing rods are between 6 and 10 feet in length. Longer rods improve casting distance and, in some instances, cushion for fine lines — 4- or 6-pound test. But don’t count out shorter ones, especially those less than 7 feet long. They’re easier to handle around overhanging cover, such as docks and branches, and when fishing lures worked with downward twitches such as topwaters and jerkbaits.

You can find spinning and casting rods in nearly every action-power combination. However, you’ll be better served with a spinning rod when your lure and line are light and a casting rod when both become heavier.

Don’t get too caught up in whether the grip is split or full and the line guides that the manufacturer used or similar details. In the scope of choices, those are small variables more closely tied to personal preference than overall performance. So, use what you like.

Reels

While a casting or spinning reel’s performance can be traced to specific characteristics, such as the number of bearings — the more, the better — weight, and material, pay particular attention to two when balancing one with rod and line. They are gear ratio and inches of line retrieved per handle turn. Both reveal how speedy you can retrieve your lure.

Gear ratio is the easiest way to tell a reel’s retrieval speed. Take, for example, two casting reels — though this applies to spinning reels, too — one with a 7:1 gear ratio and the second with a 5:1 gear ratio. The spool — or the bail in the case of a spinning reel — in the 7:1 reel will turn seven times for each turn of the handle, and the spool in the 5:1 reel will turn five times for each turn of the handle. So, if you turn both reels at the same speed, a lure towed by the 7:1 reel will move faster than if the 5:1 reel retrieved it. While quickly spinning the handle will make a 5:1 reel keep pace with a 7:1 reel, you’ll find maintaining that pace uncomfortable.

But to truly measure a reel’s speed, you need to consider the inches of line retrieved per handle turn. That’s because spool diameter affects retrieve rate. For example, the circumference of large-diameter spools is more significant than those with smaller diameters, and every time it goes around, it picks up more line. So, a reel with a slower ratio but bigger diameter spool can out retrieve one with a faster ratio but smaller spool. Even the amount of line — more makes the spool larger — affects retrieval speed.

Faster reels are better for vertically presented lures, whose stop-and-go nature creates the need to collect slack line quickly. Pitch a jig into a clump of aquatic vegetation, for example, and while it’s free-falling to the bottom, the line jumps. One crank of a fast reel will clear any slack line so you can get a solid hookset. On the other hand, slower reels create a mechanical advantage for hard-pulling horizontally presented lures such as big-bladed spinnerbaits and deep-diving crankbaits. They also keep you from quickly retrieving a lure in cold water when slower presentations often generate the most strikes.

Line

The final component — and some say the most important — to consider is line. Every inch you use needs to be strong, but you can use its other characteristics to select the perfect match for your outfit. The three fished most by bass anglers — monofilament, fluorocarbon, and braided — do certain things best.

Monofilament line has been around since the 1930s and remains a popular choice. It’s available in many colors, from completely clear to highly visible yellow or blue. There are even camouflage versions, whose alternating earth tones help it disappear in the underwater environment. It floats, which is vital for fishing topwater lures, and it has some stretch, which helps keeps treble hooks locked into fighting bass. It’s a better choice for horizontally presented lures than those presented vertically.

Fluorocarbon line is the newest of the three. It has nearly the same refractive index as water, making it almost disappear underwater, the best prescription for line-shy bass. It has less stretch and abrasion resistance than monofilament, making it a good choice for single hooked lures fished in and around heavy cover. It also sinks, helping crankbaits, for example, run deeper.

Braided line is the workhorse of bass fishing. It’s nearly indestructible, making it perfect for fishing vertically presented lures, such as jigs and Texas rigged soft plastics, in the heaviest cover. But its best feature is its complete lack of stretch. It can be used with horizontally presented lures, though a slow-action rod should be used to absorb shocks and keep hooks from being pulled from the bass. Braided line offers the most sensitivity, making it valuable when vertically lightweight fishing finesse lures in deep water. It packs more strength than a monofilament or fluorocarbon of the same diameter, so you can jump to stronger line without losing the flexibility and stealth offered by smaller diameter lines. It’s extremely visible underwater, despite being offered in shades of green, brown, and smoke. You can color it with a permanent marker to address that or add a monofilament or fluorocarbon leader in clear water. The latter is the most popular choice.