Arizona Nitro Pro Matt Shura has quite a reputation for scoring big in winter tournaments. How? He fishes where almost no one else fishes – out in the middle of the lake. He’s even had guys stop and ask him if he was broken down and needed help. “Nope,” he says, “I’m just fishing.” There are a couple of ways to find these fish, he explains, and several ways to try to catch them. Here’s how he goes about it.

Matt is old school, he says, when it comes to electronics – he started in the 80s with a paper graph, and he has stuck to standard 2D imaging with his Lowrance Touch 12s – one on the console and one on the bow. Matt looks for fish anywhere from twenty-five to sixty feet deep in the big western reservoirs in winter. The depth of your lake may be different. That doesn’t mean that no fish will be up shallow, he emphasizes, but when you can find deep fish and learn to catch them, it eliminates a lot of your competition.

Finding Deep Fish

First, Matt watches his graph all the time, especially when he’s idling. As he’s coming out of the ramp area, he watches for bait fish. Baitfish, he says, will usually be a nice big, round shape on the screen. Those are shad that are not being bothered. They are just hanging out. Wherever they are, that is the depth that the bass will most likely be at. Matt targets prime winter areas like deep flats out by the channel just before it drops off, the big flat areas in the middle of large coves, breaklines, walls on flats, and cuts where the bass can corral the baitfish.

Shura puts the trolling motor down on likely areas and zig-zags back and forth, watching the graph and looking for baitfish and bass. Ideally, he’d like to see “spaghetti noodles” – fish actively chasing shad. Generally, though, he sees those round schools of unmolested baitfish.

Matt says that although when you find those baitfish, there will usually be bass nearby, those bass don’t feed all day. They may just be hanging around nearby, keeping those shad corralled. If one comes out, they go after it, which keeps the shad in place. He calls them cowboy bass. He has been known to sit on a school of shad for up to six hours, waiting for the bass to start eating.

Zig-zagging is the primary way to find deep bass. The other way is by accident. He’s found schools of active bass out over a hundred feet deep, but the bass are at forty, chasing shad. On several occasions, he’s caught a limit of big fish out of a single school like that, and there is no one else around for hundreds of yards. Matt says this middle-of-the-lake scenario is needle in the haystack, but it still pays to keep your eye on the graph while you’re moving.

Spooning For Bass

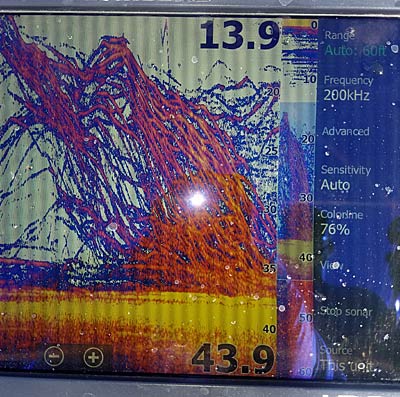

When Matt sees a ball of baitfish, he’ll drop a spoon down just above or below them. Matt says you should be able to see your spoon on the screen, and if you can’t, you need to play with the settings until you can. Turn up the sensitivity. It’s crucial to be able to see what your bait is doing. A spoon outside the ball is a separated shad and more likely to be targeted by a bass. Sometimes when he does this, the ball of baitfish turns to “dust” – it dissipates, which means that bass or something is attacking. Usually, this is when he starts to get bit.

His spoons are simple: he likes Bass Pro Shops Strada spoons in silver for clear days and white for cloudy days, both in either ½- or ¾-ounce. He doesn’t drop the spoon right through the baitfish – he goes to one side or keeps above the school. On a nice flat near a drop-off, he’ll cast the ½-ounce spoon to about twenty feet, let it hit bottom, then hop it back. If he sees a solid signal while doing this, he’ll reel it in and drop it right down to the fish. Sometimes he’ll just let it sit right in front of the fish. How do you tell which end is the front? On a graph with color, says Matt, blue is the weakest signal, and red and yellow is the strongest. The yellow end is the closest when a fish moves toward your bait.

Matt says a lot of shad die off during the winter and flutter to the bottom. This leads to what he calls “crumb eater fish” – bass that hangs around at the bottom waiting for shad to flutter down. These fish on the bottom are easier to catch, and he’s caught giants fishing spoons right off the bottom. Bass are a lot like chickens, he says – if one gets hooked and starts fighting and carrying on, the others think they’re missing out on food, and they all start coming over to see what’s happening. He and Steve Foutch caught over 200 bass on spoons in one area this way. Matt says it’s easy – if you’re in 50 feet of water and your spoon quits falling at 30, set the hook! The cool thing about spoons is that you don’t catch just bass – you can get crappie, yellow bass, stripers, catfish – almost anything.

If you can stay on these schools of active bass, you can catch a ton of them. He uses a HydroWave and sets it on the “schooling shad” sound because it keeps the fish in the area longer and more active.

Spoon Fishing Tips

First of all, don’t use braid. What you want, says Shura, is for the spoon to rip like a jerkbait, but at any depth, you please. You want the line to load up when you pull, then snap back. Secondly, but just as important, is to use a spinning reel. The spoon needs to fall freely and flutter down, and the spinning reel is key to that whether you’re fishing a Strada or a Kastmaster. The Strada is his go-to bait, but if the fish are very slow, a Kastmaster can make a difference because it falls slowly.

He uses 8-pound-test mono or fluorocarbon and a swivel clip for spoons. The swivel clip helps cut down on line twists, which can be a problem with spinning gear and heavy spoons. Also, he always puts red Gamakatsu treble hooks on his spoons. The ½-ounce Strada is his favorite, and he puts a size six red Gamakatsu treble on it. On the ¾-ounce, he uses a size 4. The ¾-ounce Strada is what he uses when the fish are very active – he can get it down to them faster.

One of his most killer spoon secrets isn’t technically a spoon, but that’s how he fishes it. It’s a Rapala Jigging Rap – a slender, shad-shaped bait, heavy for the size, with a single hook in the nose, another on the tail, and a treble on the belly. The tie-on is on top. On the size 7, he upgrades the belly treble to a #6 red Gamakatsu and bends the front hook out just a tad – which seems to give him better hookups. The size nine Rap already has a size 6 hook, so he switches to a red Gama for that one, too, without sizing up. The same color applies with this bait–shad pattern (or your local baitfish) for clear days and white for cloudy days.

The Jigging Rap falls like a rock and flutters. When you rip it, it glides. The beauty of this bait is that it covers water not only vertically but horizontally as well. For instance, Shura says, if you’re fishing thirty feet deep, the Jigging Rap will glide sideways three to four feet as it falls. You can cover much more water with it, and bass loves it.

For trees, brush, and other stuff that spoons can get snagged on, a one-ounce Crippled Herring is ideal because you can shake it off the trees. It also clunks on the wood and gets attention. He changed the single hook out to a size 4 red Gamakatsu hook.

Finally, the Silver Buddy blade bait and the Little George tailspin bait are fantastic around smallmouth bass. He casts them out, lets them fall, then rips them back. Just pick up the rod tip, feel the vibration, let it down, then pick up the tip again. You can also slow-roll these baits and tick the rocks or yo-yo them back, but not as aggressively as the bigger spoons.

Matt has brought some big sacks to the scales in winter, and that’s because he has spent a lot of time on the water learning to read his electronics. He says there are a lot of good videos out there to help you read and adjust your electronics, and the rest is just experience and patience. Once you know what to look for, you’re halfway there, so keep an eye on that graph next time you’re out, and don’t be afraid to stop in the middle of the lake if you see something worth a second glance.

BassResource may receive a portion of revenues if you make a purchase using a link above.