A shallow lake lined with bulrushes. It’s an iconic bass-fishing image, maybe second only to a stand of flooded cypress trees covered with Spanish moss. Many lakes have at least a bay or bank where you will find emergent grass, whether its bulrushes, water willow, or arrowheads, and they aren’t all in Florida. From the far North to the deep South, from East Coast estuaries to the California Delta, you’ll find stands of grass growing out of the water filled with bass. Some of the best that I have fished are on Lake Champlain, a short cast from Canada.

While you can find emergent grass in many places, it isn’t all the same when it comes to fishing. Like other bass-holding cover and structure, not all of it is productive. Finding prime locations with bass takes preparation, exploration, and some knowledge. Your extra effort will be rewarded with some of the biggest bass in the lake.

The Best Beds

From a distance, all emergent grass beds look suitable for bass. But when you examine them closer, that’s not what you’ll see. Water depth is the most crucial trait of a productive stretch of emergent grass. Deeper stretches hold more bass, especially during summer, when water levels are typically lower. But don’t get tricked by submerged grass, such as hydrilla or milfoil, which grows around emergent grass. It can make the water look shallow, but that’s not always the case. Move closer, and you’ll see that the shade created by the emergent grass has kept the submergent plants from growing and revealing the actual depth of the bed.

Keep your eyes open when you first approach a bed of emergent grass, especially toward the outside edge. That’s where you’ll see bluegills and other panfish weaving their way through the stalks. They are often an indicator that bass are there, too. Watch for the grass to move. You'll see it shake if it is thick enough as a fish swims through. It’s not always a bass; bowfin and carp love to borough in these beds, too, and can be spooked by your boat or lure. But any moving grass is worth at least a cast.

Where emergent grass beds grow is as important as how they grow. Bass are particular about the parts they use. The most productive are the points and pockets made by the grass. You’ll want to spend more time fishing them, just as you would any you come across while fishing down a rock bank with a spinnerbait or crankbait. Bass use them as ambush points to feed. The best points are windblown and near deeper water. The best pockets are covered with bits of floating grass, which have collected to form a mat or folded over stalks.

Bass are found inside emergent grass beds as often as along the edges. Key on thicker clumps of grass or anything different. For example, a log washed in, or a dock surrounded by grass can congregate bass. Even uprooted clumps can be bass magnets. They create what amounts to an undercut bank, casting a shadow, creating a clean bottom, and digging out more depth. Also, fish where different grasses mix and form an edge. An area of lily pads surrounded by bulrushes, for example, can be a hot spot.

The inside edges, both close to shore and those surrounding openings within the bed, are worth fishing, too. They are often overlooked, mainly because they can be challenging to fish. It’s that solitude that makes bass holding there more aggressive and stubborn. They’ll refuse to leave, even when the water is so shallow that it barely covers their back, thanks to the protection provided by the thick grass.

When To Fish It

Bass arrive in emergent grass beds as soon as the water temperature warms into the high 50s in spring, and they’ll stay till it becomes too cold, as long as there is enough water depth. When the water level drops, they will assemble in deeper sections. Post spawn to late summer is the best stretch to fish emergent grass. Water levels are relatively stable then, along with water temperature. And the beds are at their most developed, offering the most cover.

During low-light periods, such as the morning, evening, or overcast days, bass cruise the edges of emergent grass beds, often venturing away from the bed. They may be more active at these times, but that also means they will be in more places, making them harder to pinpoint. Once the bright afternoon sun shines, bass retreat into the bed, seeking shade for safety and as an ambush point. That makes them more predictable but not necessarily easier to find.

Don’t be too concerned if you don’t get a bit on your first pass down a beautiful stretch. With a typical emergent grass bed offering so many targets to fish, it’s possible you didn’t make the “right” pitch. And with such heavy cover, the bass aren’t easily spooked, so you can turn immediately around and make a second pass when you’ll see new targets and offer lures from different angles. Sometimes that’s all it takes. It also is common to leave the bed for an hour or so and quickly catch your limit upon returning. So don’t give up.

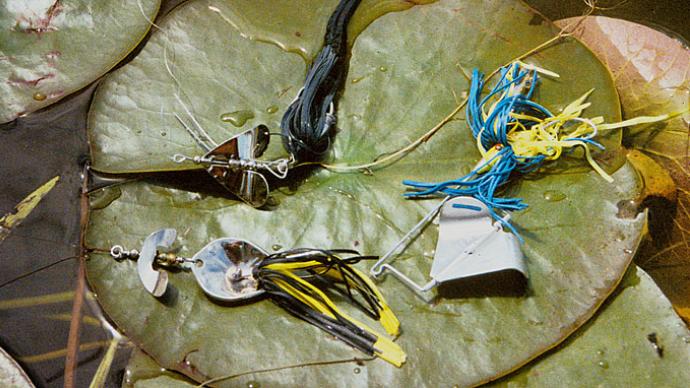

What To Throw

Emergent grass is the perfect place to flip and pitch. It offers an almost endless number of targets to fish, and the dense cover masks heavy tackle. At the 2015 Bassmaster Elite Series tournament on Lake Havasu, the Colorado River impoundment along the California and Arizona state line, Alabama pro Aaron Martens keyed on flipping tules — bulrushes — on his way to winning the event that finished on Mother’s Day. He believed the bass were eating baby red-wing blackbirds that fell from nests made in the grass. Whether or not that was the reason the bass were there is up for debate, but his lure of choice — a punch rig consisting of a heavy weight pinned with a bobber stop, sliding skirt, and Texas-rigged soft-plastic lure — is the best you can throw in emergent grass.

Punch rigs are weedless and have the same profile as many of the foods bass in emergent grass eat, including bluegills, crawdads, and even baby birds. Creature baits and craws in green pumpkin or black with red flakes are good choices for punch rigs. Pay close attention to the size of the weight you use. Like fishing in submerged grass, you need enough weight to ensure your lure makes it to the bottom. If it’s too light, you might think you’re moving it along the bottom, but it’s hidden in the thicker canopy of grass, out of sight of bass below.

Heavier weights are just as important if you throw a jig and trailer or Texas-rigged worm in emergent grass. When selecting a worm, avoid ones with long, curly tails. They tend to wrap around individual stalks, keeping them out of the water and ruining casts, which increase frustration.

Whatever style of soft-plastic lures you Texas rig, be sure to peg your weight. That will keep the weight and lure together and prevent the lure from hanging up on stalks. Don’t peg the weight tight against the lure. Instead, leave about a half-inch between the weight and lure. That will give your lure just enough freedom to keep moving. Weight placed tightly against the eyes of hooks rob lures of action. That also goes for Texas rigging tubes, an often overlooked option for fishing inside emergent grass beds. With a sleek shape, they slide into places where other lures snag. And you don’t need a giant tube. The 4-inch models used for smallmouth will flip fine when threaded on a 2/0 or 3/0 heavy gauge extra-wide gap hook.

Most bites on these bottom-bouncing lures come on the initial fall, so watch your line as the lure sinks. If it stops before you think it has reached the bottom, tighten the line. That will free your lure from the grass or reveal the bass chewing on it. If high pressure — barometric or angler — slows the reaction bite, try letting your lure sit motionless on the bottom. Sometimes called “dead sticking” or “soaking,” this can trigger wary bass to bite because micro-currents slowly move the trailer and individual strands in the skirt while you aren't moving the jig. Another option, especially when there is a mat mixed in the emergent grass, is to yo-yo your lure, pulling it to the underside of the mat and then letting it fall back to the bottom.

Regardless of what you pitch into the grass, you’ll want a baitcasting rod and reel. It’s better suited for winching bass out of thick emergent grass. You’ll want a long rod, too. An 8-foot flipping stick is not a bad choice. It will help you lob your lure farther into the grass and offer leverage to pull bass back out and over thicker patches. But a longer rod means the tip will move farther than a shorter rod with the same amount of hand movement. So keep your movements shorter, so you don’t move your lure too fast and far. Spool the reel — a 7:1 gear ratio model will decrease the time you spend retrieving your lure and increase the number of pitches you can make each outing — with 65-pound test braid or 20-pound test monofilament or fluorocarbon line. These lines' low stretch and toughness mean surer hooksets and fewer breakoffs, which will put more bass in the boat. The edges of bulrushes, for example, are surprisingly abrasive.

Hollow-bodied frogs and Texas-rigged toads give emergent grass bass something different to look at. Fish them across points, in pockets, and along edges. They also work in open water that’s within an emergent grass bed. You can fire them across the thicker sections, work them through the holes, and then bring them back through thicker grass without snagging.

Other options are weightless or floating worms, especially when the water is clear or during post-spawn when bass disperse, females looking for isolated places to recuperate, and males aggressively chasing down anything that might eat the fry they are guarding. You can cast them far on braided line and spinning gear. Swim them along edges and across points, and pause them in pockets.