The location of schools of bass can be most predictable during long periods of consistent weather patterns. I usually save up vacation time until the summer and average being on the water at least one day, if not more, during the week and on weekends. Over the last five years I have found Lake Fork (Texas) to be one of the best and consistent lakes for midday fishing I have been on since Palestine (Texas) was in its prime.

You could set your watch for various groups of fish and catch 20 to 30 in several upper-lake spots. From July through September, schools of large bass were all over the place in Birch Creek, at the dam, and under any of the major bridges. I therefore was primed for a great summer and worked my schedule accordingly.

I checked on several schools of fish in early May and, as expected, they were just getting into a couple of summer haunts. The next time I tried the spots was on May 16, 1999. I caught 25 or so fish out of secret hole number one. These were between four and six pounds. I found nothing at secret hole number two. My explanation was it hadn't gotten hot enough yet to concentrate them. Boy was I wrong!

I was involved with trying to piece together the puzzle of what happened at Sam Rayburn in the late summer and early fall of 1998, but never dreamed we would be looking at the second major bass die-off in one of our best bass fisheries within a year.

The Rayburn event resulted in a die-off selectively of largemouth bass and no other species. The episode occurred during a major heat wave, with low water conditions and with a noted loss of hydrilla. I did an article on this hydrilla issue and ended up getting all sorts of explanations as to the cause. My experience with Rayburn goes back to the time when there was still green timber and I would drive over from college and stick my 5-1/2 on the back of a rent boat. Then while in Houston I fished it extensively. In June of last year I found it to be the same old Rayburn. By October I never saw a school, or found any concentrations of bass.

The stories I uncovered about the cause of the die-off included wide spread spraying of the lake to eliminate hydrilla or in the surrounding forest. The hydrilla didn't cut much interest since the lake had been so low, most was on the bank anyway. Several folks finally got responses from the management agencies for the national forest, which indicated limited spraying a considerable distance from the lake.

Then we had the fisherman "catch-and-stress" concept. Really couldn't get anyone to identify what major tournaments occurred during this period, nor how the bass managed to swim 10 to 15 miles from the site of most major tournaments before they died in the mid-lake areas. The argument that stress was caused by low water and high temperatures didn't wash either. The lake has been extremely low several times and that wasn't the only hot Texas summer. Also, if hot water was a player, how do fish survive in power plant lakes where the temperature often greatly exceeds that of other lakes?

I concluded in the article (to the chagrin of everyone who had a pet theory) that the fish had to be dying from some sort of infection.

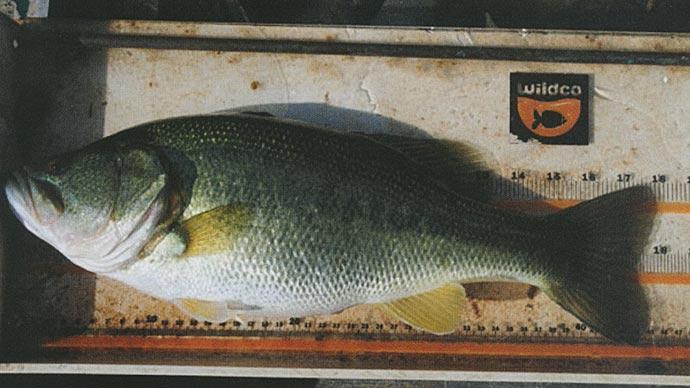

That brings me to Lake Fork in the summer of 1999. On the first weekend of June I began to notice some dying bass near the dam. It isn't uncommon to find some bass that die after the stress of the spawn, but these weren't acting right. Their bodies were torqued, so that the fish were in a bow shape, as though their muscles had been paralyzed on one side.

The events began to unravel over the next few weeks with more bass dying. Like Rayburn, it was species specific. Unlike Rayburn, Fork was slightly above full when it started and the water temperature was eight to 10 degrees below that of the same time the previous year. Some fish are going to die from various causes in a lake, but a major pollution or environmental cause kills various species, not just one.

The fishing got progressively worse during the summer, but I made a commitment to myself that my summer was going to be spent tracking the process on the lake. Certain things became immediately obvious. The fish kill affected only three-pound plus bass. It also occurred from one end of the lake to the other. Fish were coming up in the back ends of creeks, in shallow water, and deeper open-water areas as well. My weekly stints were from Highway 19 in the upper end to the back of Coffee Creek, Little Caney, Wolf, and all creeks on the Mustang side of the lake.

Fork has been an outstanding summer schooling fishery with many of the schools being comprised of appreciable numbers of fish, some even being five-pound plus bass. A very interesting spot for schools has been under the major bridges where one could, from June through September, see numbers of bass chasing shad during the afternoon.

I have not seen a school break under one of the bridges since the die-off began. In fact, with the exception of a small area in Birch Creek and an occasional small school in Dale, the lake has looked devoid of school bass.

Both the Sabine River Authority and Texas Parks and Wildlife began collection of bass, and releases in the media kept referring to the "limited number" of bass in the kill, stating the worst was over. Actually, I found a nine, three sixes, and one seven dead in Dale Creek as late as August 31.

In late August, after the first in-state tests of specimens were negative, a positive finding was observed from tests at Auburn University. The conclusion was that the bass had a viral infection. The first report of a largemouth iridovirus (LMBV) was in 1995 in bass kills in four southeastern states. We know about virus-induced diseases in man such as colds, chicken pox, measles, mumps, and rubella, but it might be helpful to briefly look at the culprit.

A virus is a very small organism, which can only grow and multiply inside of a cell. It essentially tries to take over some of the genetic mechanisms of the cell to manufacture more of the virus as opposed to the normal products that the cell genes make. A virus is simple, yet very tough. It is a survivor, and has sometimes been considered the ultimate predator in that it can sustain itself for long dormant periods and then activate when the right target is present thus controlling complex cells, which it infects.

So what do we know about this bass virus, and maybe more importantly, what do we not know?

I sought information from two Texas Parks and Wildlife officials. Dr. Larry McKinney, Senior Director for Aquatic Resources and Dan Jones, Resource Protection Biologist who is coordinating much of the study currently ongoing at Lake Fork.

The virus was first isolated from Santee-Cooper Reservoir in South Carolina and 12 reservoirs in Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina and Mississippi in 1995.

Fish collected from Fork in June and July were also found to be positive. Fish were also sampled from the hatchery in a quality control check to see if it could have been a source. This is a scary thought, but the contribution of hatchery-spread Whirling disease among trout fisheries in Colorado is well documented. I understood the hatchery fish are at present negative.

Tests are also being done on bass from several other lakes including Rayburn and Toledo Bend. Department officials advised me, as I was working on this article, that Conroe bass also have the virus.

There are some basic scientific questions that I posed to agency officials. Remember this is a new event so the fact that there weren't clear answers is not a condemnation, but simply a true status of the perplex confusion regarding the problem. Perhaps the best way to approach the problem is to list the questions and give the departmental thoughts and my own scientifically thought out proposals based on my observations and a little common sense.

Q & A Session

Dodson: Where did the virus come from and how is it transmitted?

Texas Parks and Wildlife: It was first documented in 1995 and we have no idea how it got to Texas or how it seems to skip from one lake to another. Similar viruses have been reported in some aquarium species in California (guppies, etc.), so it may have been brought in by bait supplies-minnows, etc. It is not impossible that areas with close contact between fish such as live wells could conceivably result in passage from fish to fish since we assume it infects fish either orally (gills or in food) or by skin contact.

Dodson: All of these ideas are reasonable, except that it is impossible for me to envision how an introduced food source could spread over the entire take to induce disease at the same time and in only one species of fish. The livewell concept is a scary one, but usually people don't keep bass on Fork and only in limited numbers of tournaments after which they would be released.

This doesn't have to be a new virus, but rather as with many new diseases simply popped to the surface by finding a host that it finds to its liking and eventually kills. There are numerous viruses that are carried by hosts without greatly threatening the host and some that only become activated under certain conditions, and when in the right species of animal. How was the virus diagnosed?

Texas Parks and Wildlife: The samples were sent to the vet school lab at Texas A&M University for analysis by electron microscopy. This data was negative, but was a reasonable first approach. The technique is quite restrictive in that they were looking for the scattered virus rather than using Biotechnology techniques, which would be much more sensitive. These types of bioassay tests were the ones conducted by Auburn University that confirmed the virus was present.

Dodson: With this event, a further emphasis should be placed on developing a state-of-the-art molecularly biology section to serve as diagnostic support, but also genetic data actions needed to give better tools to fisheries and wildlife management folks in the next century.

Fishing and hunting are major sources for the state and should be treated as a priority industry. Did the bass die from effects of pollution?

Texas Parks and Wildlife: No direct correlation has been determined.

Dodson: While our lakes and watersheds are increasingly more at risk from pollution, it should affect other species not just bass. What effects did stress have on the die off?

Texas Parks and Wildlife: I get stressed just hearing this overused term, but in reality stress can weaken the immune system in any animal and an inherent dormant virus can become active. An example is a fever blister. The cause virus that lives in infected humans activates when we have a trigger effect. This could be from the effects of a cold or even an event such as severe sunburn or wind-blown drying the lips. The virus causes the sore then it goes away and lurks in body ready to emerge again.

In the case of both Rayburn and Fork the fish died much after the major biological stress period post-spawn and thus were in a time of more stable survivability, the summer and fall.

In the case of Fork, the initiation the die-off occurred when the water was considerably cooler than the previous year and the lake was full.

Dodson: Have water samples been tested for the virus?

Texas Parks and Wildlife: No!

Dodson: Have baitfish such as shad or even parasites that attach to the bass been tested?

Texas Parks and Wildlife: No!

Dodson: I still can't figure out what could carry the virus and spread it over the entire lake. It makes no sense that there are enough free virus in a body of water so that they can spread upstream and into the backs of even the smallest cove. It also doesn't make sense that if a good source exists as a carrier in that the smaller fish would also not be a target. Insects can carry viruses, but the grasshopper swarm that covered east Texas occurred after the die-off began and while the catfish enjoyed their presence on the lake no catfish appeared to be dead from eating them on any of the lakes. What happens after such a viral infection?

Texas Parks and Wildlife: Re-occurrences of die-offs didn't seem to occur in some of the southeaster lakes, but the potential exists.

Dodson: Check the tournament weights on Rayburn in the spring of 1999 following the 1998 die-off. There was a major loss of five-pound plus fish. See how many 20-pound limits you find from weigh-in before and after the die-off. Present reports indicate the smaller bass population may be expanding, but it will be interesting to see what happens in the next two to three years.

As far as Lake Fork is concerned the hope is that the die-off ends. The question then becomes what is left of the fishery? If something hasn't happened to the smaller bass, why didn't they school this summer and why were reports in the papers from some of the guides on the lake noting catches of six to eight fish per day?

Does the virus affect Northern strain bass, or are the die-offs occurring in lakes with predominant Florida infusions? Texas Parks and Wildlife doesn't know if native bass are immune.

Texas Parks and Wildlife: It most likely isn't linked to Florida strain because they have been around a considerable time as stockers in Texas and also no one has reported bass kills in Florida. This may well be a virus that has mutated and jumped species, or somehow activated in affected bass of a certain age.

I have tried to give an overview of the agency's response to a series of hard questions. I have also given you my observations and ideas as a fisherman who stayed on top of this one, and as a scientist. After having said that, I share the frustration with Texas Parks and Wildlife officials that there is so much we don't know. There are some things that I can state explicitly.

While some spokesperson in the Texas Parks and Wildlife played "pass the blame to fishermen" for the Raybum event I got a different and rational discussion from both Dr. McKinney and Mr. Jones concerning Fork. They know we have a problem and weren't afraid to say, "We don't know," to my questions.

There was a coming together at Fork of fishermen, merchants and state agencies to try to determine the cause of the die-off. I wish I could tell you this is all behind us and Conroe isn't happening and Toledo Bend, downstream from Fork and 20-plus miles from Rayburn, is safe. But the time for "sugar coating" and providing "snow jobs" should be behind us.

Fishermen, and concerned citizens, should be ready to do what ever we can to support guys like Dr. McKinney and Mr. Jones and other fisheries biologists who are trying to figure out the source of the virus and ways to control it. We may be in deep trouble since finding the source may be the only reasonable "cure."

In the meantime, we can hope survivors in the lakes develop immunity to the virus and that they pass that immunity to their offspring.