The groundhog has spoken, saying we’re having another six weeks of winter. If you’re snowed in, and your fishing hole is frozen over, don’t despair: use this time to prep for a great fishing season. Trapper Hooks pro Eddie Johns spends more time doing off-the-water stuff to improve his fishing than most guys. First, he’s the guy with decades of fishing notes and maps detailed on paper. Going over these notes and discovering patterns based on moon phases, weather, and other details have given him insights into chasing bass that few can boast. Eddie spends time researching those lakes when he can’t be fishing his favorite lakes, so he knows where to go come spring.

Lake Research

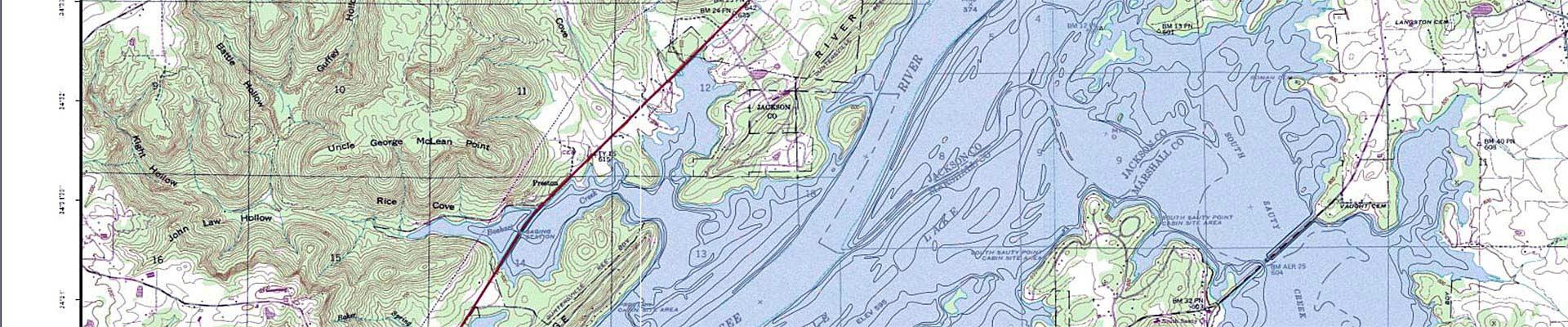

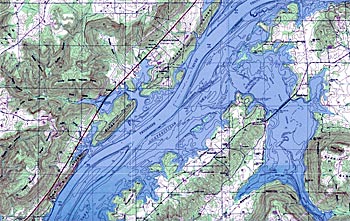

Maps are available for many large lakes and rivers, but what do you do if your favorite place has no such thing? There are tons of options. First, Johns says one enormous resource could be your local university. They often have old maps available that could show exactly what your local lake looked like before it was flooded. This means you would have details such as roads, culverts, bridges, buildings, graveyards, and even picnic areas (with concrete tables, perhaps), which are probably still underwater and holding fish.

Eddie gets detailed information from the Army Corps of Engineers, including a book of maps showing details of surveys taken pre-dam. This book has pages and pages of detailed maps that are invaluable to fishermen. Depending on where you live, a little research should tell you who to contact for maps of areas that are now lakes. For instance, the Tennessee Valley Authority says you can file a Freedom of Information Act request for a specific map. You go to www.tva.com, or you can request specific maps by contacting the National Archives in Atlanta at atlanta.archives@nara.gov. In either instance, you need to be very specific in your request.

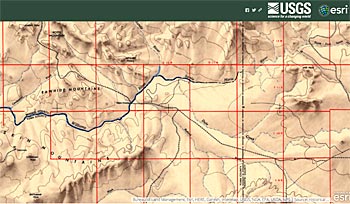

Another way to get detailed maps of lake contours, old roads, etc., is to make a custom map at mytopo.com. You can search any place by name and center your map anywhere, then choose size, scale, etc. Make sure to choose the option to include contour lines on lakes. You’ll be surprised how detailed these maps are, and you can ask them to include all kinds of information and even make a hybrid topo/satellite photo map. Another site to try is called oldmapsonline.org. Once you search for a place name, they will show you a map and a sidebar with a list of maps, including the date. It’s incredible what they have there. The USGS has a great website that lets you see current and historical maps of just about anywhere. It even includes a slider bar so you can view both simultaneously while using the slider to make the overlay more or less transparent. It’s amazing. Check it out at https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/topoview/.

In addition to viewing, printing, or buying maps, you can research a lake by finding old records of tournament results on that lake if it’s big enough to have them. This is equivalent to listening to dock talk, but it isn’t ALL going to be lies. Focus on the areas where the fish are caught during different seasons. A map can show you a likely spawning flat, but it can’t tell whether it’s mud or gravel. If bed fishermen are always in a particular arm, you can guess it has good spawning areas. If the tournaments are enormous, you’ll likely be able to find footage of the winner, and it’s hard to lie about where you are when you’re being filmed there.

One last way you can research a lake is by downloading one of the many fishing apps that allow users to share locations, catches, techniques, etc. There are many of them – some are free, some are not. Head to the app store and be sure to read all the reviews and do some online research as well. Make sure that, in addition to all of this, you resolve to start keeping a book of your own. Keep track of details such as where you caught the fish, its size, lure, technique, depth, weather, wind, etc. Include moon phase information about fronts, too. If you do this for a couple of years, you will be amazed at how much it helps you, not just on one lake.

Research The Fish

Catching bass is about getting them to eat, so it stands to reason that the more you know about the things they eat, the better you’ll catch them. Eddie pays a lot of attention to crawfish for this reason. Will he ask himself – have the craws dug in for the winter? If they have, there won’t be much of a jig bite. That means he’ll have to look for balled-up baitfish. He says the craws burrow into clay banks when the water is in the low 50s and below. When the temps go up to the mid-’50s, the males are out on top of rocks (but not slimy green ones), which is when to throw a jig. Water temps around 55 to 62 are when he likes to throw a jig and pig.

Johns says you need to study baitfish and craws to see how they react to different water temperatures and the length of the day. This drives their lives; if you can figure out where the baitfish and craws are, you know exactly where to fish. Are 63 degrees different in the fall and the spring? You need to keep notes. Research the dominant prey on your favorite lake. Find them; you find the bass. What does the food look like? What color is it? When does it spawn? How does the weather affect it? Take a note from a fly fisherman’s book and note when insect hatches occur. Bass may not feed heavily on the tiny insects, but they’ll eat the baitfish that swarm up to grab those bugs. Keep detailed notes on all of this; it will help you on any similar lake.

Eddie Johns finds plenty to do even if he can’t be out on the water. He researches the lakes, the food, and the fish. Call or email your local university, the Corps of Engineers, or whoever dammed up your favorite lake. You’re likely to find a wealth of information about what’s under that water, which might be free. Johns says there is a small fee occasionally, but they’ll usually send you links or at least direct you to the right source. Do your homework while the water is hard, and once you get out there, keep records, so your knowledge keeps growing. A good fisherman can learn on the water or off.