| Mastering the Skip and Slide |

Skipping a lure across the surface is like skipping a stone. The more splats and "pitty-patters" it makes, the further it goes. Most anglers can pick up the basics in an afternoon with intense practice. But then comes the finer points of controlled direction, distance, and accuracy. That takes much more practice. |

Whether an occasional weekend competitor or a full-time professional on tour, every angler ponders the age-old question every time they launch their boat: "Where do I find the bass?" It's a puzzle with many variables to examine. As witnessed by the chatter among fishermen at the weigh-in, there is no single answer.

Experienced bass anglers know that looking to shallow cover may often be part of the solutions. That's why flipping and pitching techniques have become so popular.

But what if the best shallow cover was configured in such a way that it was unreachable by ordinary casting, flipping, or pitching? The casual angler will drop a lure close to the edge of the obstruction and then move on to an easier target. The dedicated tournament angler, however, realizes the bass-hiding potential of such spots and analyzes the situation in more detail. Skipping may be an option.

Meet the Skippers

Using a cast that bounces across the water's surface, skipping gets a lure further back into low-hanging cover than conventional presentations.

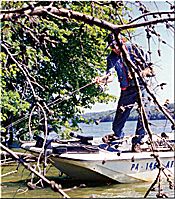

"Placing a lure exactly where I want it in an impossible-to-pitch situation by using a low trajectory cast to skitter the bait across the water's surface. That's how I define skipping," says Rob Genter, an accomplished tournament angler from Tidioute, Pa. With more than two decades of competition, Genter is known as a shallow-water technician.

Dave Lefebre is Genter's consummate rival among northeast anglers for the shallow-water skipping crown. Lefebre can skim the surface with a jig and drop it into the tightest corner of nearly impenetrable cover. But rather than using spinning tackle like Genter, Lefebre skips with a free-spool casting reel. This feat leaves every boat partner wondering how he does it.

"In addition to the sidearm skip, I do power pitching," Lefebre explains. "The bait does not skip like a flat stone but slides across the surface."

On New York's Chautauqua Lake, a dock fisherman's paradise, Lefebre has the distinction of winning 80 percent of the tournaments he has fished there in the last ten years and never finishing lower than third in all but one event.

Lefebre and Genter each have distinctively different approaches to presentation. Genter takes a finesse approach by fishing a site thoroughly with a light-weight, slow-sinking bait. On the other hand, Lefebre is a speed skipper, fishing rapidly with fast-sinking baits and covering lots of ground. Both systems work.

The Where and When of Skipping

"In northern latitudes, summer is the peak season for skipping because the greatest number of bass are shallow, but I also skip during the spring and fall," Genter explains. "Docks and moored pontoon boats are my number one and number two targets for skipping. Overhanging trees, particularly willows and blow-downs, are also productive — as well as any mass of brush and roots submerged along the shoreline. The more tangled the cover, the better I like it because it means fewer anglers can reach the interior to entice a strike."

Genter explains further: "Every single dock you look at probably has six to 10 individual targets to hit — several support posts, a swim ladder, clumps of floating vegetation, shadows, and so forth. I prioritize each target based on my ability to get the bait in and back out without hanging up and whether a flipper could usually reach the target.

I'm looking for the oddball or subtle bit of cover that others cannot reach. But if I hang a bait before I get the bite, I spook the fish under the dock."

Always concerned not to irritate cottage owners, Genter stresses that a lure should never be left snagged on a dock, tie-rope, or a boat's propeller.

Lefebre also places docks and boats on his priority list. "Many anglers think they can attract bass from under docks by quietly dropping a bait along the perimeter or swimming it along the edge. Sure, they get bitten often enough to continue believing they are drawing out all the bass from under the dock or pontoon boat. But that just isn't so. Unless you are getting your lure way back into the furthest comers of the low cover, then it's not being noticed by the majority of bass."

Skipping is not the sole method of presentation for Lefebre. His use of a baitcaster to skip was an outgrowth of flipping and pitching. "As I was going down a bank pitching to stumps, logs, and brush, I would come to a situation that could not be fished effectively any way other than a skip cast. Rather than lay down the pitching rod and pick up a spinning rod, thereby losing precious time, I forced myself to learn to skip or slide a jig with my pitching rod."

Using the same rod to alternate between pitching and skipping, Lefebre effectively utilizes skipping the entire fishing season. In addition to docks, he skips or slides his baits through culverts, beaver lodges, spatterdock beds, dead falls, and even the rubble of collapsed lakeside retaining walls.

Rod and Line Picks

Genter has experimented with many rods, looking for the perfect one for skipping. He currently uses a 6 1/2-foot, medium-heavy spinning rod.

While he struggles with different rods every few years, Genter has settled on what he considers to be the best line for skipping. A thin diameter 20- or 30-pound test Spiderline Braid will be found on his reels. He ties baits directly to the superfine, avoiding the additional knots a mono leader would create.

"Having used monofilament for so many years, I am convinced I give up bites by using Spiderline," Genter says. "However, Spiderline has enabled me to hook bass from tight spots that I never could do with stretchy, less-sensitive mono. It's a trade-off, but one I willingly make." Genter does keep one skipping outfit rigged with monofilament for extremely clear water situations, especially when dealing with smallmouth.

Lefebre has a different opinion. "Skipping into all sorts of natural and manmade cover is brutal on line because it's always rubbing something. I can inspect it with mono and immediately identify whether a nick or abrasion has weakened the line. Braided lines, however, often look frayed shortly after being used. I can't tell how strong it is by inspection. I've lost too many big fish with braided lines. Besides, it's not a good thing to skip on baitcasting equipment."

Using a baitcaster with all brakes completely turned off, Lefebre says loops are impossible to avoid when skipping, but he has learned to fish monofilament loosely spooled on the reel. If using a superfine, loops and backlashes lead to impossible-to-unravel tangles.

Lefebre's line pick is 15- or 20-pound test P-Line because of its strong knot strength, better abrasion resistance, and less stretch than regular monofilament. Rod-wise, Lefebre's stick must perform the double duty of skipping and pitching.

Bait Choices

Four- to 6-inch worms, craws, tubes, and soft stickbaits in subtle baitfish or earthy tones are the soft plastics most often used by Genter for skipping. "A streamlined bait skips better. The fewer tentacles and appendages hanging on a bait, the easier to skip. I like craws, but the flopping claws reduce the distance somewhat. Tubes are great, but they lack the weight and bulk of some of the other baits. Therefore, a tube generally needs a 1/6- to 1/8 ounce internal weight."

Genter takes an ordinary bell sinker for an internal tube weight and smashes it flat with a hammer. "You end up with a weight just like an expensive internal weight, but for a fraction of the cost," he adds.

Although he prefers to keep the weight hidden inside the plastic, using an external weight on some baits is necessary. In these instances, he employs a Top Brass Peg It to securely hold a small cone-shaped worm weight against the head of the bait.

Skipping across the water places torque on soft plastic. If not held in check, this results in the bait sliding down the hook shank. To prevent this, Genter rigs his baits with a 3/0 or 4/0 Gamakatsu EWG hook. The tip of the point is skin hooked in the plastic to reduce hang-ups.

Favoring Berkley Power Baits, Genter doctors any other soft plastics with scent to encourage bass to keep the bait in their mouth. Having bass hold the lure is critical to his overall system. Because of the odd positions that skippers find, the hookset's angle must be thought through to obtain a positive result and not break the rod. The longer a bass holds the bait, the better the angler can maneuver the rod for the best hook-set angle.

Lefebre's bait of choice is different from Genter's. One of his top choices is a 7/16-ounce Stanley Jig with a large Zoom Plastic Chunk. He also creates many of his creature jigs using various soft plastic components and appendages, striving to develop different-looking baits from anyone else on the lake.

"With my big jig, I'm looking for aggressive fish buried way back in cover," Lefebre explains. "When other skippers throw smaller finesse stuff, I go in behind them with a big jig, bounce it twice on the bottom to stir up the silt, and anticipate a strike. Then I pick it up for another skip. I don't soak a bait. I don't finesse it. I keep moving to cover territory."

Lefebre drops to a 1/8-ounce custom-made jig and an Uncle Josh No. 11 frog if the bite is extremely slow. The smaller profile and slower sink rate will usually do the trick. But if that fails, his fallback bait is either a Senko or French Fry worm on a 4/0 or 5/0 hook. Lefebre uses wide-gap offset Gamakatsu hooks exclusively in soft plastic.

Bait color is essential to Lefebre. Generally, he matches his jig or worm color to the tint of the water. In brown-stained water, he goes with brown or pumpkin pepper. In greenish-stained water, green pumpkin is a favorite.

Black or pearl white are his picks for crystal-clear water.

Lefebre concludes by saying: "The interesting thing is that while Rob Genter uses spinning tackle with braided line and finesse baits, and I use casting tackle with heavy monofilament and flipping jigs, we are both trying to solve the same problem. That is getting our lures to bass that have not been disturbed by flippers and pitchers."

Content provided by Bass Fishing Magazine, the official publication of FLW Outdoors