The milfoil bed snaked its way out in front of the boat, marking every twist and turn of the drop that tumbled into Lake Ontario’s clear water. Using the trolling motor, my partner positioned the boat perpendicular to it so we could cast to its prime spots.

I launched a spinnerbait toward its shallow side, hoping to connect with one of the big largemouth known to live in this particular spot. My partner grabbed a pistol grip rod, using as much effort as possible to fling his lightweight offering. It landed not far away, where the aquatic vegetation formed a point along its deeper edge. He peeled plenty of line from his reel to keep it slowly sinking. A 4-pounder ate it before it reached the bottom.

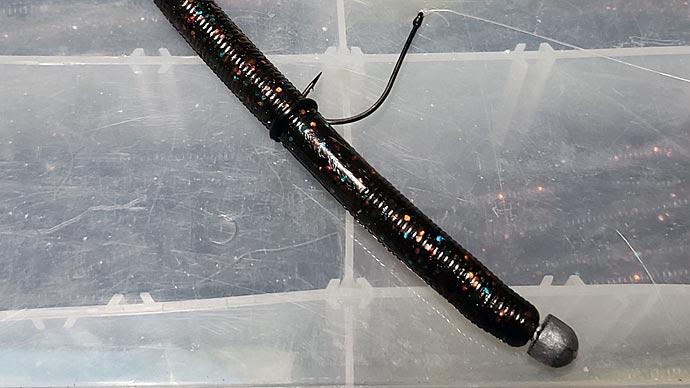

My partner’s lure was a 6-inch Creme Scoundrel — the tough plastic worm credited with launching the soft-plastic lure business. He stabbed a 3/0 offset-bend hook through its center and added no weight. While his go-to soft-plastic finesse lure was slightly unorthodox for the time, he had the tournament checks to prove its power over the bass. He was cashing in on wacky rigging before wacky rigging was cool.

Anglers still catch plenty of bass by rigging soft-plastic lures wacky style, but the process has evolved. Specialty tools, such as the one that applies O-rings to keep hooks from tearing up lures, have been introduced, making circle hooks more popular with freshwater anglers.

You can add the wacky jighead to that list of changes. It’s probably best represented by Jackall’s Flick Shake, though many manufacturers have introduced versions. Regardless of who makes the one you tie on, they make the bass-catching wacky rig more effective.

Why it works

Cutting his tournament fishing teeth in the West, Bassmaster Elite Series angler Brett Hite doesn’t hesitate to finesse fish, despite recent successful attempts to cast himself as a vibrating jig expert. When he chased bass-eating baitfish around brush on the main lake and secondary points that went from 5 to 80 feet on Lake Hartwell during the 2015 Bassmaster Classic, he probably picked up a wacky rigged Yamamoto Senko, the most popular soft-plastic lure for the technique. Using his electronics, he watched it flutter down, with the help of a small inserted weight, and bass swim up to intercept it. The technique helped put him in seventh place when the scales stopped spinning on the last day.

The wacky rig is one of the countless finesse presentations used by bass anglers. Their colors, sizes, and rigging create a natural look that bass can’t resist. Take the omnipresent shakey head. With a heavy head and light tail, it sits on the bottom like a feeding baitfish, oblivious to an approaching bass. The time-tested split-shot rig is no different. Its soft-plastic lure follows a weight crimped on the line, swimming, and gliding as it pleases.

The wacky jighead is no different. Place it near the center of a soft-plastic lure and watch its head and tail flutter independently as it moves through the water. It also causes the lure to sink in a unique way slowly. Instead of falling head first like nearly every weighted soft-plastic lure — from grubs on leadheads to Texas-rigged lizards — these fall horizontally, like most underwater creatures, move. It also keeps the lure active once on the bottom, which gives even the most pressured bass enough incentive to bite. The added weight increases casting accuracy and expand the depth range of a technique that once was confined to shallow water.

Choose your components

It must work with all its related components to catch the most bass with your wacky jighead. A regular leadhead jig will work, but one designed for the technique will treat you better.

A wacky jighead has a short-shank hook made of light wire, which holds a super sharp point capable of catching inside a bass’s mouth without a hookset. Attached to the hook, just below its eye, is a weight, usually spherical or conical in shape. Its compact size and location keep its mass near the soft-plastic lure, which adds action. Most have a single wire weedguard. It must sink slowly, so start with a 1/16-ounce model. Go heavier only when necessary, such as when the wind makes casting difficult or the current washes away a lighter weight before it can sink.

Spend time choosing a soft-plastic lure. You want one that generates action on its own. The Flick Shake worm, for example, is slender, creating the silhouette of an easy meal. But look closer at its design. Its head is more prominent in diameter than its curved tail and slightly flattened along its length. All of these traits work together, creating a shimmy as it sinks. But it’s not the only choice for wacky jigheads.

Senkos, especially the thin version, are good choices, too. If you hold one by the thicker end and slowly spin it between your fingers, you’ll notice a slight hook in the tail. Rig it so that hook curves down when it sinks. That will help it catch the water it needs to create more flutter. Straight-tail worms work but stay away from the shortest models. Longer worms extend farther past the jighead — the pivot point — giving the ends more freedom to move. Avoid soft-plastic lures that require forward movement for action, such as jerkbaits and ribbon-tail worms. And don’t be quick to choose the softest plastic, as you might be inclined to do with other finesse presentations. They will fold around a wacky jighead while it sinks, eliminating any chance for a fluttering action. That’s the reason my partner chose a tough Creme Scoundrel.

Quiet presentations and light weights mean you’ll need a spinning rod for wacky jigheads. Choose one about 7 feet long with fast action and medium power. You’ll use its snappy tip to cast the light lure farther, while its powerful backbone will steer bass from cover. Match it to a high-speed spinning reel with a large front drag, which will run smoother and start with less effort than a rear drag.

You can load the reel with monofilament or fluorocarbon line, but braided line and a 2- or 3-foot leader of 6- or 8-pound test monofilament is a better choice. That material floats, which will further slow the lure’s sink.

Put it together

When a wacky jighead is rigged correctly, the worm will shake and flutter to the bottom. It may take some experimentation to uncover the best spot for the hook in each type of worm, but that’s as complicated as it gets.

Start by finding the worm’s center. Then insert the hook slightly toward its thicker end. The bulk there will overcome the extra weight that would kill action in the thinner tail if your soft-plastic lure has a flat — or flatter — side. Rig it, so it faces down while sinking. Like with the Senko, that will cause it to catch more water, exaggerating its flutter.

Don’t make choosing a color complicated. You might want bubblegum, for example, fishing for smallmouth hanging around boulders or clumps of aquatic vegetation scattered across a rocky flat. But for the most part, natural hues, such as green pumpkin, pumpkinseed, or watermelon, will treat you best. They add to the presentation’s natural look.

How to fish it

A wacky jighead’s compact size and slick-sided soft-plastic lure combine to make it one of the easiest lures to skip under overhanging trees and docks. It may take some practice to make one act like a flat-sided stone on a still millpond. If you’re having trouble, try making more gentle casts. A forceful one tends to push the lure farther into the water on first contact, causing it to stall. Instead, try a soft roll cast that builds momentum from start to lure release. Also, try moving farther from the target. That will flatten your lure’s trajectory, making for a softer first touch.

Once your wacky jighead is where you want it, let it flutter to the bottom on a completely slack line. And when it’s there, don’t be in a rush. The worm’s ends will continue to move, attracting nearby bass without you doing a thing. After you’ve waited at least 15 seconds, take out the slack and pull it about 2 feet off the bottom, trying not to move it very far forward, and let it return to the bottom on the slack line. Repeat the process, creating the fluttering fall as many times as possible. The bottom line is to go slow. Moving these lures too much will convince bass not to strike them.

Some bass will hit hard enough to send a solid tap into your rod’s handle. But most strikes are subtle. You won’t feel them until you raise your rod tip and remove the slack from your line. This is a big reason you need a high-speed spinning reel — so you can catch up to them regardless of where they’ve swum — which is filled with sensitive braided line. It has nearly zero stretch, so even the slightest tick on slack line is transmitted back to your rod.

Braided line helps in one more way. It gives you the courage to fish wacky jigheads in the types of heavy cover that other finesse lures won’t tread. Don’t panic when you connect with a bass that’s moved deeper into cover. Gentle pressure will put you farther ahead, leading rather than forcing the bass away from objects that will saw your line in two.

There is no wrong place to fish a wacky jighead, though visible targets in shallow water are most popular. Try them offshore, like Hite did at Hartwell, but be sure you have a crucial piece of structure, such as a tip of a point, or cover, such as an individual brush pile, lined up for your casts. This lure won’t draw bass from a distance. Instead, it proves most irresistible when it falls right to where they are holding.