In the last article, we told the story of the development of Bremer Pond. Being in the North Country, thoughts of winter dissolved oxygen (D.O.) levels and winterkill are never far from our minds. Thus, we set up a research study last winter to see if we could get some hard evidence, rather than just speculating about what happens under winter ice.

We really had two primary research questions.

Question 1

Is there any sign of supercooling from the circulation system? A 1/2 horsepower circulator keeps water open in the barge/dock area of the pond (Figure 1), and may have some minimal effect on D.O. levels. We suspected not, but wanted to check to be certain.

If the topic of supercooling is new to you, consider reading more articles on the topic. Here's the short version. Winter aeration systems keep an open hole in the ice on our northern ponds. This hole allows sunlight penetration so algae and aquatic plants can still provide oxygen to the pond during winter. The concern has been the potential for supercooling if too much circulation is applied to the pond. Water is most dense at 39°F and water on the bottom of a pond is actually the warmest during winter. When that bottom water is lifted to the surface, it melts a hole in the ice. If the volume of water we circulate is high, we may actually lift too much of that 39°F water off the bottom. Water passing near ice at the top of the pond cools. If the overall pond cools so much that water temperature at the bottom drops substantially below 39°F for extended periods of time, then supercooling has occurred. Such cooling may negatively affect fish, perhaps to the point of winterkill. Many fishes cannot survive extended time periods in 33-34°F water.

Question 2

Shallow groundwater flows through this excavated, pit-type pond, even during the winter. Does this create a problem because of low D.O. from inflowing water?

Generally speaking, ground water does not contain dissolved oxygen. Certainly, ground water from deep wells does not contain D.O. However, we now suspect shallow ground water moving through sand and gravel substrates does contain oxygen. If not, then the movement of new water into the pond must be insufficient to impair oxygen levels. So, we wanted to see if there was a problem or not.

To conduct this study, a truly interested pondmeister (that's Dwight, of course) had to brave the Minnesota winter. He measured ice thickness and took temperature and D.O. readings at roughly 1-week intervals. Both temperature and D.O. were measured at the pond bottom, in the middle, and then just below the ice (surface).

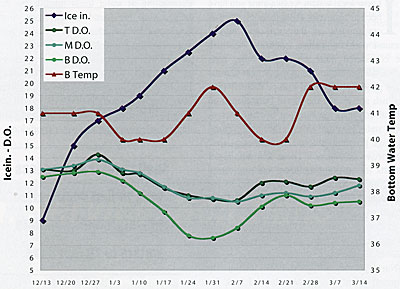

So, what did we learn from Dwight's winter exposure? Well first of all, the darn winter of 2008-2009 started early and ended late! Ice thickness peaked at 25 inches on February 7 (Figure 2). "Normal" thickness ranges from 12 to 16 inches, so it was indeed a cold winter. We actually were fortunate to choose a tough winter. If low D.O. problems were ever going to occur, they would be mostly likely during a long, hard winter.

Now, let's turn to some of the "facts" about winter D.O. and temperature in ponds. Did they hold true? Was the water just under the ice coolest? Yes, it was always near 33°F. Was the water warmest at the bottom? Yes, it was warmest, but actually a little warmer than we expected (Figure 2)! Science tells us 39°F at the pond bottom, but we found it to be a couple of degrees warmer. After checking the calibration on the meter, we can only guess that the incoming ground water actually keeps the gravel pit a little warmer on the bottom. The only other explanation might be some solar heating of the pond bottom, but that is beyond the scope of our study. At the least, this warmer bottom water should make for happy fish in Bremer Pond!

Another common fact about winter: the D.O. always is lost from the bottom of the pond first. Did that happen? It sure did (Figure 2). The lowest bottom D.O. we measured was 7.6 parts per million, so again those were some happy fish! D.O. levels certainly never got low enough to impede fish movements or cause them to not use the bottom waters.

Did you notice the increase in D.O. levels on February 14 and 21? It was most visible in the bottom waters, but can be seen at all depths. What happened to cause that'? Well, the spike was caused by a week-long thaw that actually raised the ground water table and also caused the adjacent Rock River to flow. The increased ground water flow raised the ice pack up and away from the pond edges (Figure 3), increasing D.O. levels.

What about our two research questions? First, we certainly found no evidence of supercooling with that relatively small circulation system in Bremer Pond. Second, we also found no evidence of low D.O. from the incoming groundwater. Water quality, in terms of both temperature and D.O., was superb.

One additional observation before we close.

Most anglers assume that fish become more "dormant" in the winter. In this pit-type pond, they remained relatively active, at least based on underwater video taken through the ice. However, that is probably a story to be saved for the future.

The winter was a tough one for Minnesotans. However, the fish in Bremer Pond likely never noticed a thing! As with all of Mother Nature's work, seasons always change and spring did return to Bremer Pond (Figure 4).

Now, what are we going to do to keep Dwight busy outside next winter? Send all your great ideas to D. Willis, care of Pond Boss magazine! Dwight is a glutton for punishment -- or could it be that he is just plain passionate about Bremer Pond?

Dave Willis is department head in the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences at South Dakota State University.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine