"Life is like a box of chocolate. You never know what you're gonna get." That quote, made famous by Forrest Gump, can apply to your pond.

Stay with me, this story gets better, I promise. Over four decades as a fisheries biologist I've seen some pretty interesting stuff buried in the digestive tracts offish.

I've seen rusty hook shanks coming out of the back end of bass. Red and puffy back there, I'd bet those bass were tickled pink when a little tug frees them of those mostly-digested fishing accessories.

I knew at fourteen years of age I wanted to make a living messing with fish. That was the same year I saw my first weird thing in the belly of a channel catfish. We were at our little weekend place on the Brazos River, between Granbury and Glen Rose, Texas. The river began to rise, and the current soon became pretty swift. It was late summer, and on that Saturday night I'd traipsed through some wild sunflowers with a flashlight and coffee can, catching those big yellow grasshoppers that were everywhere that time of year. I threaded one on a big hook with a heavy weight, pushed the button on my Zebco 33, and lobbed a long cast into the river, which immediately shoved it downstream, and deposited my offering about two feet from the bank.

No way there'd be any fish there, it was the wrong side of the river. The channel was on the other side.

It was getting late, so I did what most 14-year-old boys probably would do. I laid a concrete block on top of my rod handle and tied the rod to a willow limb and went up to go to bed.

The next morning, I went down to the river and my rod wasn't under that block anymore. It was in the river. I grabbed the cord, retrieved the soaking-wet rod, and saw the line way out in the middle of the river. My heart pounded as I started reeling. Whatever was way out there on the business end wasn't quite ready to give up. After a few minutes of fighting both the fish and the current, I was the proud recipient of a nice-sized catfish. It weighed four pounds, ten ounces—not bad for that part of the river or a teenager. I even got my picture published in the local fishing periodical.

My dad and I hung that catfish on a nail in a tree and cleaned it. I'd already become fascinated with what fish ate, but this nice channel catfish was especially surprising. It had a pocket gopher in its belly. A dadgum gopher! Who would have thought of that? And, the greedy little squirt ate a grasshopper, too? When the river rose, it must've flooded a gopher's place, and the catfish was in the right place for a hearty meal.

I'll always remember electrofishing a lake in upstate New York with several fisheries students. All the Largemouth bass were cookie-cutter, carbon copies of each other, mostly 12-13 inches long, and thin—except one bass with a pooched-out belly. When we stopped to weigh and measure the fish, I had a young fisheries student hand that fish over. I looked down its gullet and saw feathers. Honestly, two little black feathers. I gave the belly a little squeeze and a drowned barn swallow popped out. I held it up for all to see. The fisheries student offered a quick grin and gave it a shot, "I didn't know bass could fly!" We got a good belly laugh over that comment—I still chuckle every time I think of it.

I went frog gigging around one of my hatchery ponds once, way back when, and caught two-dozen bullfrogs. I brought them up to clean them, planning to eat frog legs that night. When I clean a frog, nothing edible is wasted. Skinned, and gutted, we fry all the legs. Being that biologist-guy, I looked at what they had eaten. Most of them had crawfish in the bellies, and several had some of my prized coppernose bluegill fingerlings inside. But one, with a rock-hard lump in its belly, had a different surprise. As I used the skinning pliers to pull its skin away on the tailgate of my pickup truck, a newly hatched turtle popped out and fell on its back. The silver-dollar-sized green amphibian quickly flipped over and tried to run off. That turtle was still alive. My little niece wanted it. She named it Jonah— appropriate.

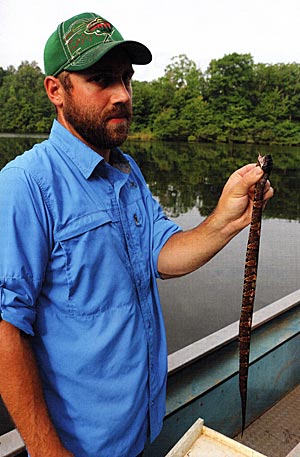

Another time, electrofishing a small pond about fifty miles west of home base, we collected the typical stuff from overcrowded bass lakes—overcrowded, skinny bass. One was quite plump, so when we stopped, I pulled it from the live well first. Opening its mouth, stuck my thumb inside, took a look, and immediately dropped it. I might have also said a select epithet about the same time. The netter on the front of the boat started chuckling. He asked, "Why'd you do that?" I picked up that bass, aimed it at him, and he figured out the answer to his question. That bass had just swallowed a fourteen-inch diamond-back water snake, and its head was sticking out of the throat of that bass, alive as it could be. He recoiled as I had.

I've seen three-inch bass try to swallow a two-inch bass, and both of them perish. Predator fish will eat pretty much everything you think they will, plus lots of stuff you don't think about. If it's moving, and fits into its mouth, a Largemouth bass will eat it. Typically, in a bass, we'll see everything from different types of fish (of course), to remnants of crawfish. I've seen five-pound bass trying to swallow a twelve-inch gizzard shad. It can do it, but it might take a while.

I've seen a cottonmouth water moccasin coughed up in a live well, courtesy of a six-pound bass. I've pumped many fish stomachs over my career, and I've seen everything from insects to twigs to pebbles.

So, just because we work hard to grow a good food chain to support our fish, they'll take the opportunities that avail themselves. If you have an ounce of biologist in you, pay attention to what your fish are eating when you catch one. Compare notes and you'll learn something else about your pond and its inhabitants.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine