Look at your pond as a garden. You prepare it, plant it, nurture it, and watch it grow and mature. You also harvest it. After all, you'll eat tomatoes, peppers, green beans, potatoes, and onions from the garden, right?

Think about your pond in the same light, too.

From time to time you need to harvest fish from your waters. The biggest difference between pond and garden is how you judge what needs to be harvested. Tomatoes turn color. Tops of onions fall over. Fish grow into certain size classes.

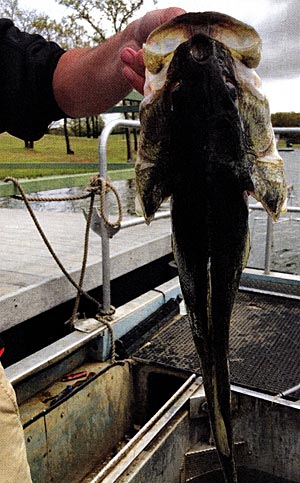

How do you judge what to harvest? This concept seems a bit misunderstood by many. Once a pondmeister overcomes the stigma of eating a bass, the next step is to figure out which ones to take and which ones to leave.

Judge fish based on pond goals. Here's one important tip to start. If you have a bass pond, your first-stocked fish deserve the opportunity to die of old age. Well, that's not totally, entirely true. Let the females grow up, grow large, and then die of old age.

But, judge your fish as they grow. Use the well-known tool of relative weight. Understand how much a ten-inch bluegill should weigh. Know the standard weights of your bass. Go online and find the SmartFish app for your phone. Our good friend, Wade Bales, has gone to great lengths to make judging bass much easier. The app is free, storing data is $65 per year, well worth the dollars to track your fish. If you don't want to use the app, you still need to judge those fish. You can use the app for free. Set it up, follow the prompts before you go fishing again, and then when you catch one, weigh and measure it, enter the data into the app, and it will immediately give you relative weight. If that fish is less than 90%, consider removing it.

The fundamental ways to judge your fish are based on body condition and frequency. If you are catching mostly 10-14" bass or 6-7" bluegills in your five-year-old pond, you are past the point to have a thoughtful fish-judging plan. Start it now—or pay later with slow-growing fish that won't reach their best potential.

Here's an example of how this works. Say you catch 20 bass in a morning and each one is 10-15% underweight. You decide to harvest all of them. Next trip, you catch 20 fish. 18 are seriously underweight and two are marginal. You choose to harvest all. Next trip, you catch 20 fish. 10 are underweight, 5 are marginal, and 5 are plump. Your harvest plan is working. Get that ratio down further, and you're properly judging and harvesting your fish.

Another really important factor in judging your fish after studying each fish, is to study the population as a whole as well. If you catch ten bass in an afternoon and one is horribly underweight, and the rest are average or slightly below, that doesn't necessarily mean the entire population is in trouble. It likely means one grossly underweight fish is old, sick, or has an issue as an individual. If all the fish you catch are 10-15% underweight, then you have issues with overcrowded, underperforming fish that are probably overeating their food chain. If you monitor your fish as they grow, you'll get to the point you can predict this case and beat it before the fishery suffers.

When we recommend judging fish based on your goals, that means to decide if each fish you catch is in bounds for your pond's destination. I'll always remember a conversation with fishing guru and TV star, Bill Dance. He told me about his private lake and how it stopped producing its biggest bass. As the fishery matured, he was advised to increase the size limits of bass harvested, with the goal of preventing overcrowded bass that stop growing. Each year, the length limit went up. When I asked him what the size limit was, he answered, "We are taking all fish four pounds and smaller." When I asked him why, he said, "Because we don't want the bass to get too crowded. We want plenty of room and food for the biggest bass." I leaned across his desk in his office there outside Memphis, Tennessee and said, "Bill, I didn't learn this at Texas A&M. Had to figure this out by myself" He was intent on hearing the next sentence. "Bill, a four-pound bass can't grow to double-digits in a skillet." He busted out laughing. The point I was trying to convey was that harvesting bass larger than three and a half pounds was culling the freshman team. All bass three pounds or larger should be left to grow, unless they are 15-20% underweight. And, if they are lightweights at that size, it's probably not their fault. It's the pond manager's fault for unwittingly limiting the food supply. Besides, any bass three pounds or larger are likely females. If a male makes it to three pounds, it deserves to die of old age, too.

If your goals are to have a healthy, balanced fishery, then harvest a variety of sizes, based on body condition. As long as fish are fat, let them grow. But, be on alert enough to see when their growth levels off within certain size classes. That's the fish to remove.

One fairly common question is, "What if we harvest too many fish?"

I'll always remember the first conversation I had with Ray Scott, the father of bass fishing tournaments. He preaches catch and release all over the world. I asked him, "Do you really believe in catch and release?" He popped right back, "Absolutely I do...in big public lakes where fishing pressure is heavy. In my lake, we harvest as many small bass as I say, then we double it and harvest that many more." I said, "You and I are gonna get along really well."

The point here is that when you harvest fish, there's not an end. More young fish fill those slots. Harvest should be ongoing and thoughtful for most ponds and lakes.

Judging and harvesting fish keeps the population vibrant and dynamic. That's what you want. Oh, and contrary to our being taught, "Judge not, lest ye be judged"—that doesn't hold so true for your pond. You better judge, or the pond will judge you, and you won't necessarily like it.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine