Here we are, entrenched in winter. It's a new year, days are short and we're past Winter Solstice. Soon, Punxsutawney Phil, the famous groundhog, will see his shadow and we'll be forecast for six more weeks of winter. Hunting season is winding down, college football is about to crown it newest champion and the Super Bowl isn't far away.

Winter is supposed to be a time of rest, and for much of nature, it is.

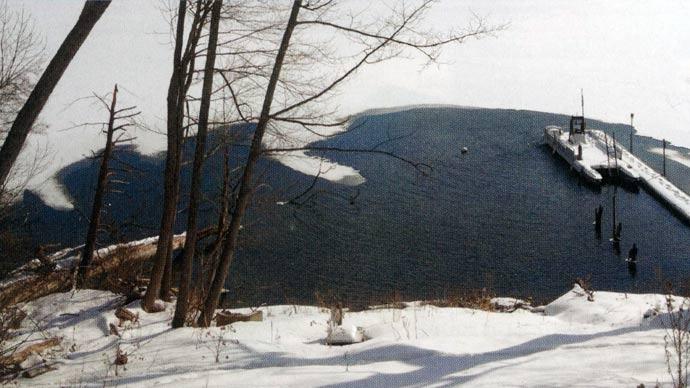

But what goes on under the ice in your pond? If you stand up, look out the window at your northern pond, you'll likely see a landscape of frigid, frozen earth, with a white layer of stuff you are growing a bit weary of, and your pond covered with a thickening layer of ice.

Being a boy from Texas, writing about northern ponds, seems a bit of an oxymoron. After all, when someone mentions "ice" in Texas, we automatically think of a glass of tea and those hard chunks floating around in it.

Back before I knew much about northern ponds, I wondered what people did in that part of the country when it got cold. Maybe just stay inside? Southerners don't really understand cross-country skiing, snowmobiles, ice-skating, or fishing with those little poles through a hole in the ice. We certainly don't visualize a campfire on a frozen pond.

But, our friends in the north do.

Do our northern friends truly understand what happens biologically under the ice during winter months? I bet some do, but some don't.

When ice forms early, as it did late fall 2018, the hard water insulates the rest of your pond's temperatures. That's a good thing. Odds are, the deepest water in your favorite hole is in the 40's. That's warmer than where we live in the south—without ice on top. Surface temperatures dropped faster than normal last fall, some dropping more than twenty degrees in less than two weeks, even in some of the larger public bodies of water. While physics demand water temperatures drop simultaneously through the water column, when it hits the low 40's, water actually hits its densest point. As it cools below 39, water expands. That's why ice floats. It's much less dense than warmer water. So, as winter progresses, you'll see the warmest water nearest the bottom as water nearer the surface expands with cooling temperatures.

In the fall months, living creatures in your pond go through an interesting process. Theoretically, your pond has the highest density of forage fish of the entire year. Spawns occurred during spring, and some in summer. Those baitfish grew quickly, and your fishery is approaching its highest carrying capacity of the year. That's the opportunity game fish need to feed heavily prior to winter. That's important because they need to build flesh and store some fat for winter as the females develop their eggs. When the temperatures drop twenty or more degrees in such a short time, activity slows to a crawl. Cold-blooded animals' metabolism rates drop, so their food requirement drops. If they haven't stored enough fat by then, they'll naturally lose weight over the winter. That's a bad thing.

With an extended period under ice, other biological things happen, too. If ice is cloudy, like most, sunlight is blocked from the water, and photosynthesis stops. Oxygen is" consumed by plants, rather than produced. When temperatures fall in winter, most microscopic plants die and fall to the bottom. That's a good thing. That's good because living greenery respires under cloudy ice and dark conditions. Respiration is the opposite of photosynthesis, meaning plants take up oxygen and give off carbon dioxide. Without photosynthesis and water contacting the atmosphere, dissolved oxygen in water becomes finite. As it's consumed by plants and animals, the volume of oxygen depletes. With extended time under ice, a pond is much more likely to experience winterkill. Winterkill happens when animals suffocate under the ice. That's a bad thing.

If ice is clear enough, rooted aquatic plants can continue photosynthesizing, producing new oxygen for all to breathe. That's a good thing.

With plants consuming oxygen under cloudy ice, or snow-covered ice, dead plankton on the bottom temporarily consuming oxygen, fish and insects breathing oxygen, your pond can run out way too early in the winter. That's a really bad thing.

Job One for northern pond owners is to assess their risk of winterkill. If your fishery is valuable to you, buy an oxygen meter, learn how to use it, and then do so. A few hundred dollars can help you decide if you need to be proactive. Check oxygen levels two or three times per week, starting at the bottom and coming up. Check your dissolved oxygen every three feet and write it down. After three or four weeks, you'll see a pattern. With good records you can predict the risk of critical oxygen depletion and winterkill.

If you project an oxygen depletion, buy an aeration system. Shop now to figure out which one is best. Here's a tip. Aeration works by moving water to interact with the atmosphere, which allows the wet stuff to relieve itself of bad gases and absorb itself of the good ones. That's a good thing.

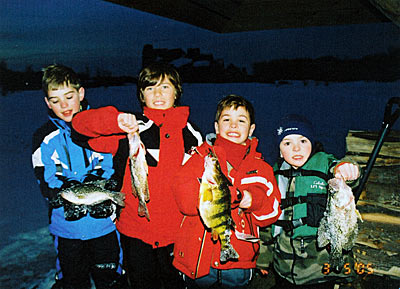

If your risk for winterkill is low, assess your fish. Yes, that means drill some holes and catch some fish. Most importantly, look at your fish's body condition. Weigh and measure some of them. Again, write it down for comparison. Winter is a great time to harvest some fish, if needed. If your fish are a wee bit underweight, think about adding some forage fish. In northern waters, fathead minnows could be a good winter choice—if your local supplier can offer them. I'll not recommend fathead minnows during warm months for an established fishery, but it can be a good idea during winter. Not only are you chumming your pond, you're adding an additional baitfish during the most sluggish time of the year.

What about underwater greenery? You should leave it alone. Any work done to minimize aquatic plants should have been done early in the fall.

One other practical tip for winter time pond management is to improve habitat. Actually, for those of you with thick ice cover, winter is a great time to improve habitat. Collect Christmas trees or brush, or native cedar or hardwoods, and build piles on the ice directly over the areas where you want to add cover next spring. Or, buy some artificial habitat. Here's your best tip. Drill a hole through the ice, tether an anchor, and wrap the brush with nylon rope, baling twine, or something to hold the pile together. One of the best ways to anchor is to drive a plastic pipe into the pond bottom and tie your brush pile to the pipe, above the ice. That way, when the ice melts, your odds of keeping your project where you place it go up.

As you figure out your risk of winterkill, be prepared to make a decision to mitigate that risk. Monitor your fish by catching and observing them. Remember, healthy fish will bite your bait—if you know how to ice fish. If you find fish on your camera and can't get them to bite, watch their behavior. Emphasized breathing is a symptom of dropping oxygen levels.

All these biological factors come together to influence your environment under water. Oxygen is influenced by plants, which are influenced by sunlight—or the lack of it. There's your biggest tip. Dead plankton and other organic matter layered on the bottom of your pond use oxygen, too. Factor that in, too. But, when that thin interface on the bottom of the pond loses its oxygen, biology becomes anoxic. Organic matter will break down, but will do it much slower. That means water above the bottom few inches doesn't consume oxygen. But toxic gases will build up in the thin layer on the pond bottom as that process continues. The bottom layer of badness will grow thicker, over a longer period of time. Because of that fact, if you choose to aerate, starting in the winter, be really careful what type of system you buy and how you start it. If your pond has a high density of fish, you could suffocate them with your kindness, inadvertently pushing that layer of bad gases upward, intoxicating the water, and pulling oxygen away, rather than adding it. That's why it's important to think about the type of aeration system you choose.

Use your winter wisely. Understand how the different aspects of biology under your ice can conspire against you and what can be done to counterattack that conspiracy. That counterattack may be nothing—but then again, it might require a strategy.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine