Nothing seems to worry northern pondmeisters more than the ever-looming risk of winterkill. I've heard true tales from most every northern state. It can be so discouraging that many people simply stop trying to manage their waters, because the risk is too great.

How do you decide whether or not to manage your northern waters based on that always-present risk? Up until a decade ago, you just waited until ice-out, and then looked to see if your fish were dead.

With winter just around the corner in northern states, now is a good time to think about what you can do to mitigate that risk. In order to do that, we all need a better understanding of exactly what that risk entails.

Simply speaking, winterkill is the consequence of dissolved oxygen being depleted under ice. What depletes it? Believe it or not, the biggest consumer of oxygen under ice isn't necessarily your fish. It's the plant life. Under ice, plant respiration is greater than photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is the natural process where greenery utilizes sunlight as energy and uses it to combine with carbon dioxide dissolved in the water to make simple sugars to fuel the plant. The byproduct of photosynthesis in your pond is oxygen. Respiration is the opposite process where plants (and animals) use oxygen to metabolize or burn simple sugars to release energy to live. When the sun doesn't shine, plants go through respiration, using oxygen from the same source as your fish—oxygen dissolved in the water.

Under ice, as long as sunlight can penetrate, photosynthesis can still occur, but it happens at a much slower rate than during the summer months. Your water under ice likely has some algae, but not the same volume as summer. As long as there's some sunlight, oxygen will be released in the water column. But here's where it gets a bit complicated. Every living thing under your ice cap respires, using oxygen. Zooplankton, bugs, plants, your fish, and one other big thing we don't think about, bacteria, are all using oxygen in your pond. When your algae bloom crashed, and when a bunch of underwater plant life died off, oxygen-consuming bacteria do what they do—they decompose that organic matter— even under the ice.

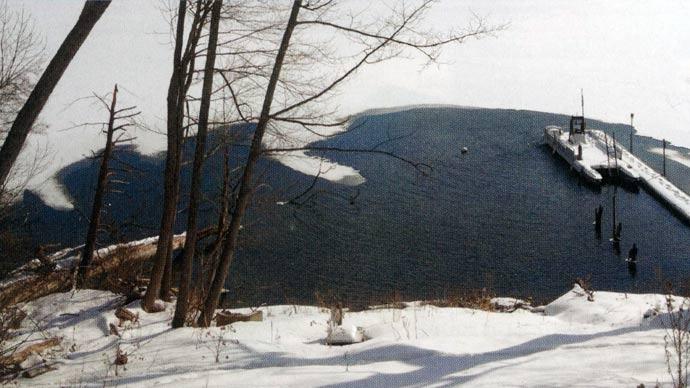

When a pond has that much going on, with a limited amount of oxygen replenished, expect dissolved oxygen levels to drop. Here's something else important to understand. Winterkill is more likely to happen in older, shallower ponds, because less volume of water holds less total dissolved oxygen. When ice lasts a long time and has snow covering the ice, your risk of winterkill goes way up. Deeper ponds have more water; thus, those deeper ponds have more oxygen and less risk of a winterkill compared to shallower water bodies. If you have a pond in Minnesota, you need as much water at least 15-feet deep as possible, and deeper is better, up to depths near 25 feet. Compare that to Missouri ponds that may have ice cover for two months, way less than those Minnesota ponds. Eight to ten feet of depth in Missouri is probably enough to not worry about losing significant amounts of oxygen to precipitate a fish kill.

The further north you live, the deeper the water needs to be to decrease risk of winterkill. However, studies over the years have shown that even in the coldest states, water deeper than 25 feet doesn't seem to impact risk of winterkill.

Keep in mind, snow plays a big role in increasing the risk of oxygen depletion. Clarity of ice is important, but our northern friends know that ice isn't always clear. That's totally dependent on weather and how the ice is formed. Add snow cover to the top and risk rises. I've watched a pondmeister in upstate New York shovel snow off his pond to make sure sunlight can beam through the ice. He had lots of rooted plants under water when ice formed that year. Just remember that clear ice allows transmission of sunlight below. That's important.

Another big risk factor is biological productivity, fueled by nutrients. In other words, the older, more eutrophic ponds have greater risk of losing oxygen over a long winter than newer, less fertile waters. You can tell a pond with lots of nutrients. It grows lots of plants.

What if you take the time and rake out as many plants as you can prior to ice-up? That's a great strategy, as long as you remove significant volumes of your plants and do it at the right time. The right time is removing plants in fall, before they have a chance to replenish via regrowth.

Lack of oxygen isn't the single cause of winterkill. When there's lots of plants dying under the ice, bacteria do what they do to compost all that greenery. As bacteria decompose plants, several different gases are the byproduct of that natural process. Methane and hydrogen sulfide are given off. Ever step into the edge of a pond where that black muck is and smell sulfur or rotten eggs? That's hydrogen sulfide. Both of those gases are deadly to fish. With lots of decaying organic matter being handled by expanding colonies of bacteria, these gases by themselves can be lethal to fish once they reach toxic level. The problem here isn't necessarily these gases, but the fact that ice traps the gases, keeping them from escaping harmlessly into the atmosphere like they do when ice isn't present.

As you are seeing, you have some decisions to make. The most obvious question is, "Why can't we just aerate the pond?" You can, but be wise about it. First, there's a thermal refuge for your fish under ice, believe it or not. Water at the bottom, in the deepest area, stays around forty degrees all winter. When you aerate, you run the risk of chilling that warm water down deep and creating enough stress on your fish to kill them. So, aeration strategy is important. Secondly, think about ice safety. You don't want any living thing to plummet through a hole in the ice in the middle of the pond. Work with your aeration company to figure out the best system and how to use it for your northern waters.

In order to make the best decisions, you need to know other factors. Think about your fish. Some are sensitive to low oxygen, others not quite as much. Trout and salmon start dying when oxygen levels drop much below 5 ppm, down to 3, regardless of the temperature. Some of the intermediate group of fish, especially walleye, some of the sucker species, sunfish, and most minnows die between 1 and 3 parts per million. Even though their metabolism rates drop dramatically during the cold months, these fish still need at least that much oxygen to survive.

There are a few species that seem to be more tolerant of even lower oxygen levels—below 1 part per million. Fathead minnows, bullheads, northern pike and yellow perch can handle such low oxygen levels.

When we know these kinds of facts, then we can develop our strategy and do what we need to do to minimize the risk of winterkill. Get rid of rooted aquatic plants, harvest some fish prior to winter, and think about a functional, safe strategy for aeration.

Otherwise, budget some time to shovel snow off the top of your ice, hoping it is clear enough to allow the sun to do what the sun does.

At least we all have a better understanding of our risk factors for winterkill, as long as Mother Nature doesn't drag out her icy attitude for too long this winter.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine