Pond ownership, like life in general, can include the good, the bad, and the ugly. We usually only like to talk about the joys of owning a pond (the good) and occasionally the heartaches that come with owning a pond (the bad). However, there is a truly sinister side of ponds we rarely see and never discuss. In this edition of Empirically Speaking, we will explore the ugly side of ponds.

During the past summer, I had more calls regarding the health risks of pond water to humans and animals than in all previous years combined. It started as the whole of the Deep South was baking in record late-season heat. It was brutal, and you had to beat the heat any way you could. For some, that meant going for a swim in a local stream or pond. Each year, millions of people, companion animals, and livestock do the same, with no ill effects. Occasionally, someone or something gets sick.

The most insidious example is surely primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, a.k.a., the brain-eating amoeba. Although visible infections are extremely rare, they are nearly always fatal. It is caused by Naegleria fowleri, a small amoeba species that thrives in very warm fresh water. This species normally eats bacteria, but it can enter the human body through the nose. Once there, it moves through the olfactory nerve to the frontal lobe of the brain. It takes from 2 to 15 days for symptoms to appear, but once they do, death occurs within one week. Unfortunately, modern medicine has not yet perfected diagnosis or treatment.

Luckily, all of my calls were just from pond owners who had seen the news from elsewhere and were worried that they might be at risk. The reality is that the chances you die from Naegleria fowleri infection are extremely low. In the U.S., only 34 infections were reported from 2009 to 2018, for an infection rate of 3.4 per year. By comparison, lightning kills 49 people per year in the U.S.

Around the same time, news stories began to circulate about dogs dying after swimming in ponds. They frolic in the water, having a grand ole time, but quickly become ill soon after. Vomiting and seizures often follow, and death shortly after. Within a few weeks, dogs had died in North Carolina, Georgia, Texas, Louisiana, and Wisconsin. People were freaking out, and sensational and often erroneous news stories fueled the flames. TOXIC ALGAE IS SPREADING ACROSS THE U.S. read the headlines. Right on cue, my phone started to ring.

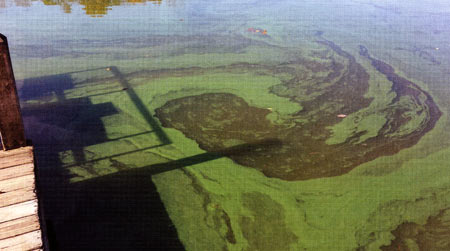

This was a classic case of cyanotoxins. Cyano-bacteria, or blue-green algae, are everywhere in the environment. Cyano-bacteria typically thrive under hot, dry conditions. These conditions evaporate large quantities of water, concentrating nutrients. There are hundreds of different species of cyano-bacteria in the U.S. alone. When conditions are favorable, cyano-bacteria can rapidly multiply in both fresh and salt water and cause blooms. Many are not toxic, while others are, and the toxic species are only toxic some of the time. They do not always release the toxins into the water. Usually, the toxins are released when the cell dies.

The unfortunate canines swam and/or drank from contaminated water undergoing a toxic cyano-bacteria bloom. Other animals, including livestock, fish, and humans, can be affected as well. Is it a risk? Of course, but only a handful of the millions of people and animals that come in contact with ponds each year suffer any consequences from cyanotoxins.

In most cases, there is no need to fear the water, nor is there a need to test for cyano-bacteria or its toxins. When asked if I suspect a pond contains cyano-bacteria, my response is, "Yes, it does." All ponds in the heat of summer generally do. As far as testing for toxins, there are maybe a dozen different toxins that might be there one day and not the next. Testing can get quite expensive.

My callers asked, "Can I use an algaecide and knock the cyano-bacteria out?" Can you?

Sure. Should you? That's a big NO. Remember, the toxin is released when the cell dies, and we do not know for certain how long the toxins persist. Not to mention that killing plankton or weeds when water is hot and oxygen is low is never a good idea. The best bet is to practice due diligence, but we will get to that later.

Before the cyano-hysteria had cleared, I began receiving word of another malady—Pythiosis. This rare and deadly disease was beginning to rear its ugly head. Caused by the fungus-like eukaryotic organism oomycete, which is more commonly called water mold, although most species are actually terrestrial.

The species of concern is the oomycete Pythium insidiosum. Although it sounds like a Harry Potter spell, this nasty organism appears to enter animal bodies via open wounds in the skin or in the gastrointestinal tract. It causes thickening of the stomach and intestinal tissues and displays symptoms that may include fever, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal masses and pain, and enlarged lymph nodes. If the infection is in the skin, it can develop as lesions anywhere on the body.

Unfortunately, this call was an actual exposure. A lady's horse was diagnosed with Pythiosis and had to be euthanized. The veterinarian told her that the infection likely came from her pond. As you can imagine, she wanted to know how to treat the water to make it safe.

Sure, there are products available that will kill Pythium insidiosum, and probably a lot of good organisms at the same time. But Pythium is found everywhere. A specialist told me, "Pythium is in every drop of water. I can go out in the parking lot just after a rain and get Pythium out of every puddle on the blacktop." You simply cannot treat all of the water.

Further, the horse was likely sick to begin with, making it susceptible to infection. Healthy animals are exposed to Pythium all of the time, yet do not get sick. There is an undefined genetic susceptibility or immunocompromising event to cause infection and disease. Chances are that if it did not get sick with Pythiosis, it would have contracted another malady.

So, what is a pondmeister to do? Should you simply never go outside again? Of course not. The odds of getting sick from a pond are extremely low, especially if you practice good, old-fashioned common sense.

To avoid amoebas snacking on your brain, stay out of hot, shallow areas in the warmest months, and try not to disturb the bottom muck when swimming in the hot summer. Try to keep your head out of the water when temperatures are hot to avoid getting water, and things living in it, in your nose, eyes, mouth, or ears. Ear and nose plugs may also be warranted.

To prevent exposure to cyanotoxins, simply avoid contact with pond water that looks, for lack of a better word, gross. A bluish-green color to the water is a clear sign of cyano-bacteria, but most cyano-bacteria are various shades of green or brown, and some even have a reddish tint, so color alone cannot be used to identify cyano-bacteria. Any time the water looks like it has a sheen, scum, mat, froth, or otherwise does not look cool and refreshing is a good time to avoid swimming. These conditions are most notable on the windward side of the pond where surface particles are pushed by the wind and accumulate.

When in doubt, practice caution. Pets should not be allowed to swim in or drink from any waterbody that is intensely green or blue-green during hot weather. Chances are the pond is perfectly safe, but it is best to find other ways to cool down. If they do jump in, it may be prudent to rinse them with clean water and prevent them from licking their fur. Another obvious red flag is dead fish or other aquatic species—if fish are dying, the water probably is not safe for you or your dog.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine