The best pond managers are artists. They have to be, almost out of self-defense. But, the best part of being a really good pond manager is that learned ability to listen. Listen not only to those experts who convey what you need to know, but listen to what that pond is trying to tell you as it does what it does during each season. In this case, listening means using all your senses to figure out what's going on under your waters.

Here's what I mean.

To guide your waters is akin to painting a picture. The pond is your canvas. Wait, that's a little too goofy of an analogy. Let's go this way. Your job as pond manager, is more like being a detective in order to solve your pond's crime. Hold on, that's not a good comparison, either. Maybe it's more scientific, poring over data to come to some logical conclusion as you subconsciously think of winning a Nobel Prize for excessive pondology. Well, that's not it, either.

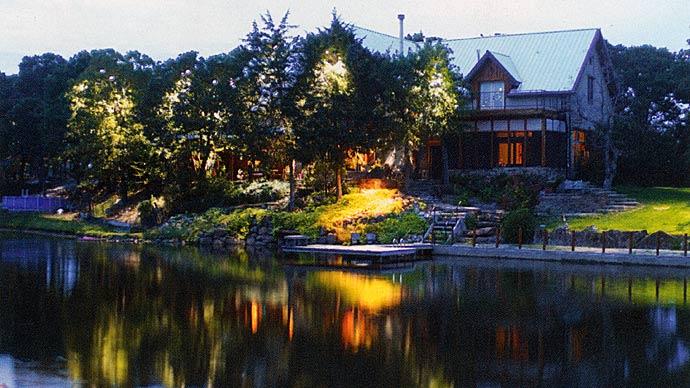

We simply want a pretty pond with big fish. That's more like it. Simple, easy, pleasing to the eye, pleasantly disrupted with an occasional big splash from that giant fish.

As I travel this nation, talking with pondmeisters, it strikes me more often than not that many folks see a pond as a means to an end. Then, they are somewhat shocked a few years down the road that there is not really an end, and their means must morph, or that precious pond becomes something other than the vision engrained in their minds some years ago.

This concept is relevant when you consider the meaning of a pond's life.

I'm trying to avoid Zen and stay with intuition to push across some points here. Pond management isn't linear, and it can be unpredictable.

Case in point—last spring wasn't really spring, and then summer started early. Ponds adjust to circumstance and opportunity.

If you can wrap your brain around some loose ends and logically tie them into a thoughtful little bow, you'll be a better pond manager. Ponds respond. That's what they do. They respond to even the subtlest stimulus. What we have to do is predict that response. Often, we evaluate our pond, see something, smell something, or assume something, and think we need to do something. Even more often, we don't see something, don't assume something, and then do nothing. Think about both those paths. We can get kicked in the proverbial teeth either way.

If we have a fundamental understanding of water chemistry and water quality, and we can see changes happening in front of our eyes, then we have a basic understanding of the medium. That's where it all starts, right? Happy water, happy life, right? That's why we investigate our options for aeration. That's why we think through a feeding program, or decide whether or not we should fertilize our waters, or maybe take out some vegetation to manage nutrient input. That goal is to keep our water clean. Then, it rains and the pond flushes. That's another change, or stimulus. The way this summer is starting, it looks like our South American buddy, La Nina, will bless a big part of our nation with a drought. High pressure systems push summer heat on our ponds. Our ponds respond to these things. The jet stream shifts, rains happen over there, and we look past the summer solstice.

We watch plants grow, and then decide what to do about it. By then, it's one of those old-fashioned Mr. Goodwrench stories of days gone by—"Pay me now or pay me later." It's the "Let them grow, or make them go," so to speak, of our underwater salad bar.

We catch a few fish, proud of our waters as we release those beauties. A few days, 'er a few months later, we catch them again and wonder why they don't look quite so fat. "Maybe it's just the season," we think to ourselves. About that time, we see a lone double-crested cormorant, diving, head perked to the side wondering why we are invading his new-found space. If we don't know what that little scout's up to, we'll never know what his waiting flock might do.

There are so many loose ends to think about, I circle back to that artist concept. Pondmeisters truly are artists, based in science, intuition, ecology, fisheries, and esthetics. While a pond may not truly be a canvas, it reveals its intentions with color, with odors, and how its inhabitants behave. Some of those inhabitants are confined; some aren't. Part of the fun of having a pond is trying to figure out what all these clues really mean. Oh no, getting back to that detective concept again. Maybe we are detectives, looking for subtle hints or little clues—trying to prevent a crime.

I'll always remember seeing a line of mussel shells along the shore of an east Texas lake some years ago. The owner strolled the shore with me. He asked the offhand question, "I've never seen this many mussels before. Does it mean anything?" I thought about it for a minute, looked over the lake and asked him a question. "Is your water normally this color?" He'd not noticed. "Yes, it seems a little darker." I picked up a few empty shells, looked at them and waded out into calf-deep water, kicking around in the mud. I found a few living mussels, much smaller than those palm-sized shells lining the shore. My brain was processing this clue. I suggested his pond had recently turned over and some of his oldest mussels succumbed. I surmised it was a minor ordeal and that all would be fine. The water color was transitional, going from what it was a few days earlier to what it will be in a few more days. Those little clues might go otherwise unnoticed. There was a faint musty odor, almost pleasant, a bit more terse than fresh turned earth. I suspected his pond was burping.

The ensuing conversations centered around concerns about water quality, the fact his bass hadn't been biting very well, and feeding around his sole feeder was lethargic. He'd noticed these things, but didn't understand what it meant. There were too many loose end clues that he couldn't put together. That's why I was invited to have a sit-down discussion with him, to help interpret what he was seeing (and not seeing), and then decide whether or not to take any kind of action.

It seems overwhelming to try to observe and absolve our waters of every little symptom. I concur, counselor. I do this stuff for a living, and still miss some important clues. The biggest take home point of this article is to understand there's a lot to learn, and there are lots of clues. While pond management is an art, we may not be the best artists, especially when those talents are science-based with a touch of Sherlock Holmes all stirred into a canvas we call our ponds and lakes. If we get stuck on all that Zen stuff, maybe we lose sight of just how pleasant our ponds really are, and maybe nature can just handle it while we sit back and enjoy a cold beverage on a steamy

hot summer day—or, maybe not.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine