The calendar is filled with important events for Kim Straley and her husband, Shawn, including one that falls in the middle of winter. “My husband can remember the first fish he caught on a bait that he made,” she said.

The couple, who owned a tackle shop then, we're searching for something to do when cold weather slowed business. So, they tried pouring their own soft-plastic lures. The first was a worm, which Shawn fished in a nearby outflow that offered open water despite the connected lake being locked under the ice. The bass bit right away, as did the bug for pouring their own soft-plastic lures. “It’s very addictive,” she said.

The couple went on to start Poor Boys Baits, hand pouring the popular Erie Darter and creating the first goby imitator for drop-shotting in the early 2000s with the help of Joe Balog and other top Lake Erie bass anglers. They purchased Indiana-based Lurecraft Fisherman’s Shop in 2005, merging it with Illinois-based Lure Parts Online in late 2021. It started in the 1960s when soft-plastic lures hit the market and were the first to offer what you need to make your own. She said it remains the world’s largest supplier of soft-plastic lure molds.

Lurecraft also sells plastic, coloring, additives, tools — everything you need to pour soft-plastic lures. Straley said business doubled because of the COVID-19 pandemic when people following stay-at-home orders wanted something to do. “We sell to individuals clear up to some large manufacturers,” she said.

And while business has leveled off as the pandemic appears to be waning, the reasons anglers start pouring remain the same. Some set out to make their creations or re-create no longer commercially available favorites. Others see the opportunity for a small business, selling what they create. And if you’ve wanted to try it, she says it’s easy to start.

Where to start

Straley said soft-plastic lure pouring doesn’t have to be expensive. You can start hand pouring into silicone molds for about $100. Stepping up to two-piece aluminum ones requires more of an investment. While a mold for small ice fishing or crappie baits may be $50, plus $70 for an injector, you can spend from $500 to $1,000, depending on the lures you want to make.

Western New York angler Charles Waldorf, whose photography graces several bass-fishing magazines and websites, started pouring soft-plastic lures about 15 years ago when he purchased one of Lurecraft’s starter kits. It included a mold or two, plastic, and additives such as color. “It was the coolest thing ever,” he said. “I enjoy pouring them and being successful [on the water] with something I made myself.”

The simplest place to start pouring is with an open mold and some sort of heatproof container such as a Pyrex measuring cup. You can heat the plastic and mix your color, glitter, and other additions. Once that’s ready, you can go straight to the mold and drizzle in the plastic. It takes practice. “Your hand has to be pretty steady,” Straley said.

The alternative is using a plastic pot. They are similar to the ones that melt and dispense lead for sinkers, jig heads, and other fishing items. But instead of molten metal, the hopper heats and holds plastic, color, and additives. They’re dispensed in a steady stream that’s easy to aim into an open mold.

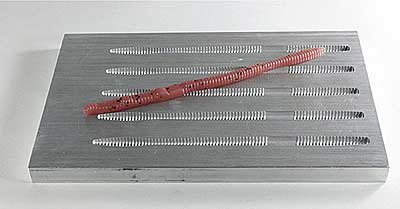

Injection molding is done with a two-piece aluminum mold and an injector, which Straley says looks like an old-fashioned air pump. It’s the rage because it produces completely round lures. Hand pours have a flat side. While bass don’t mind — plenty are still caught on them — it bothers some anglers. “It’s just a confidence thing,” she said.

You may want to make a lure with no commercially available mold at some point. It may be something of your creation. Staley said you can make your mold. There are kits to create a silicone mold, or you can have Lurecraft make one. Aluminum molds can be machined, too. But pay attention to the price, she says. The best bargain may cost you the most. It may not produce quality baits or, in the case of a lure you created, may be sold to others.

Preparing the plastic

Straley said most Lurecraft customers order their materials online and pour them in their basement, backyard shed, or basement. She said everyone wants a specific plastic for each style of bait. And while those are available, many are the same formula with different labels.

Plastic can be purchased in different degrees of soft, medium, and hard blends, which correspond to the finished bait’s texture. Straley said West Coast anglers, for example, prefer blends that produce soft baits, while most Midwest anglers want a medium blend. Medium-hard blends are used in saltwater baits, and complex blends are used for reaction baits, such as toads and tubes. “It’s easier to cut the tails,” she said.

Plastic must be heated, kicking off a chemical reaction that turns it into a solid from a liquid. Stoves or hot plates are used, but microwaves are the most popular choice for the job. The plastic is milky white at first. As its temperature rises, it turns clear and sticky and then becomes thin, about the consistency of 30-weight motor oil. “The optimal temperature is between 340 and 350 degrees,” Straley said. At that point, it’s ready to pour.

Deciding how much color and glitter to add takes trial and error. Straley recommends creating “recipes,” which make reproducing the combinations you like easier. Start with a set amount of heated plastic, counting each drop of color you add to the heated plastic until you reach the desired shade. She recommends using small measuring spoons for glitter. Once you’ve determined the correct amount, you can stir those into the plastic before it’s heated.

Salt and scent are popular additions to soft-plastic lures. Straley recommends adding salt when the plastic is hot and ready to pour. It sinks, so that helps it remains in suspension. The scent is heat-sensitive, she said. So, if you add it while your plastic is “cooking,” you’ll create a horrible smell and won’t have any in your lures. Instead, she recommends mixing it with worm oil and tossing your lures. The scent will leach into your lures over a day or so.

Lures are ready to be removed from a mold after about five minutes. Straley said you can fish with them immediately, but it’s better to wait a few days for the plastic to cure fully. That will make them more durable, and the tails are easier to cut if you're pouring tubes.

Tips for rookies

It takes skills to pour soft-plastic lures well, which takes time to learn. Practice will help you climb the learning curve. Straley has some tips to make that easier.

Straley sees new pourers make the most common mistake of not shaking their plastic before starting each batch. Plastic is a blend of compounds, including a hardener. It can settle out of plastic that has sat. Shaking puts it back into solution. If you don’t, your baits may not harden once cooled.

Don’t let your plastic get too hot. Straley said it can form bubbles, affecting your final product. She said bubbles also form from too much stirring when mixing color or glitter. And if you use an injector, she suggests removing its nozzle and pouring plastic into it. You can create bubbles by sucking plastic into it like a syringe.

Overheating can affect color and glitter, too. It can change the latter's color and cause large pieces to curl. It not only occurs during the first heating. If you work with too large of a batch when hand pouring, the plastic can cool before you finish, forcing you to reheat it. So, it’s best to work in small batches. And if you’re using a pouring pot, only mix enough for a couple of hours’ worth of work.

Safety first

While it’s easy to get caught up in the possibilities of what to pour, there’s one thing that you can’t ignore — safety. Straley said plastic comes with a safety data sheet — MSDS — explaining precautions you need to take.

Molten plastic poses the most significant risk. It’s hot and can splatter, so it burns quickly. “If you get it on you, you can’t get it off fast enough,” Straley said. She recommends always wearing protective gloves. Waldorf does when he’s pouring. He also covers his legs and feet; shorts and flip-flops aren’t pouring attire. He’s seen hot plastic drip or splatter when topping off an open-pour mold or removing a nozzle from an injector.

Straley and Waldorf recommend pouring in a well-ventilated space so any fumes from heating plastic can dissipate. Waldorf uses his garage, leaving the door open and running a fan to push air outside.

Unlimited potential

Waldorf started small, expanding his pouring-in step with his interest and skills. He has about ten molds, including aluminum ones that allow him to make laminated baits, primarily for swimbaits and drop-shot baits such as small worms. He can make them in almost any color combination, thanks to a growing selection of color and glitter. He suggests beginners start simple, testing the waters before making a significant investment.

Knowledge can be gleaned in several ways. Straley said the internet offers endless posts and videos about pouring soft-plastic lures. They are great ways to learn techniques. You also can reach out to experts and retailers, such as Lurecraft, with your questions. She often is asked about adding a heat stabilizer to plastic. Some blends contain it, she said, and it helps preserve the quality of some colors, including white and fluorescent ones, during longer heat cycles.

Straley has more than two decades of soft-plastic pouring experience, including production for companies. But it has never become an old hat. “I still learn every day,” she said. And that’s a large part of the fun. While it’s hard to beat the thrill of catching bass on a lure that you made, it’s equally enjoyable to experiment with colors, glitter, and other items, trying to create the next hot bait. “The sky is the limit … whatever your heart desires,” she said.