A fishery is genuinely a reflection of an assortment of variables. Happy water is undoubtedly the starting place. The fishery can't be healthy if the medium isn't healthy. Assuming that fundamental piece of the fisheries management equation is good for your pond, the next variable, by far, is habitat.

As goes the habitat, so goes what lives in it.

Your fishery responds to what your environment and its habitat offer. Remember that.

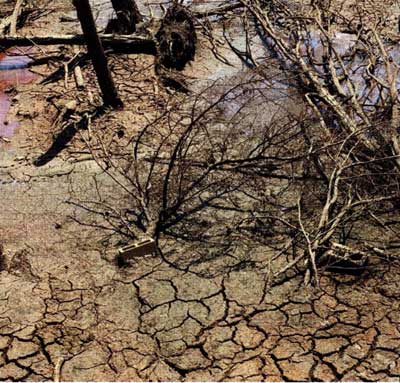

When a lake or pond is built, its organic habitat begins to degrade. That's a fact of nature. Ponds and lakes age. Some of its "permanent" habitat begins to disappear. River banks under water begin to slough. Creek beds load with silt. The lake bottom takes a different shape and contour as more dirt and organic matter flow in and settle. Brush piles break down, and standing timber dies and falls apart. Over time, habitat changes or disappears.

A perfect example of that is Christmas trees. I've been involved with several projects with landowners who collect those trees and add them to the bottom of aging lakes and ponds.

They attract fish, especially when bundled—tiny fish love to hide inside.

The needles are gone within a few months. The smallest limbs degrade and come off around 18 months under water. After three years, only the biggest limbs are left. By Year 8, all you can see is the trunk and the few largest limbs. Here's the biggest kicker. If those trees weren't standing upright on the pond bottom, by Year 5, they have collapsed and mostly sunk into the mud.

Hardwood trees are different. With some integrity in placement, bigger trees with sizable limbs withstand the test of time. So do rock piles and heavy clay cliffs and creek banks.

Over the last few years, state agencies, bass clubs, and conservation groups have dug into ways to revitalize parts of public lakes and waterways to improve catch rates.

Artificial manmade habitat is the trend.

Heaven knows I've seen plenty of older lakes whose habitat has either been nonexistent or has deteriorated due to age. Way back, bulldozer guys thought a smooth pond bottom was pretty. Some still do. Fish don't. The fishery is a reflection of habitat.

What does that mean to you and me? Depending on the lake and where it sits, it usually means the fishery isn't what we want. It can mean a heavily-silted lake covered in huge mats of pondweed. But, most of the time, it means a lake chock full of stunted bass, carbon-copy, stringy fish 10-14" long and about as thick as a knotted ski rope.

One of the friendly debates in the fisheries world is what to do for lakes whose habitat has degraded and needs an underwater facelift.

Does artificial structure work? Is it worth the money?

When a pondmeister starts the inevitable online search to buy something for their favorite fishing hole, those enquiring minds often reel in shock...sticker shock, that is.

Those different products aren't cheap.

But are they worth it?

There's the question to answer.

Several questions need answers.

First, what's the purpose? Want to improve catch rates? Or, want to catch more fish and increase your pond's ability to grow more fish...and bigger fish? That last one is the million-dollar question.

Until a few years ago, there wasn't much empirical science to prove how much habitat is enough to influence fish production in private waters. So, guys like me had to guess what a lake or pond needs to make it productive enough for that particular landowner and their goals. One credo I've lived by is that 90 percent of the fish live in 10 percent of a pond on any given day. I've seen that over and over for decades in an electrofishing boat. Still believe it. But, that 10 percent changes, based on season and other dang variables, especially water temperature. Think summer and winter.

Even today, when designing a new lake, trying to figure out how to take advantage of what nature offers for that site and how much manmade habitat to add is a guessing game.

A good, round number is to assume 25-30% of a lake's bottom surface area should have some of the different elements of habitat, primarily peripheral, but taking advantage of a lake's depth as well. That percentage is measured above the thermocline, by the way. Fish can't thrive beneath the thermocline, so the best habitat is mostly peripheral.

Several companies have seen the niche to manufacture artificial habitats and make products available for our marketplace. Each has done their research.

And there's been some empirical research done on private waters as well. So it may not be enough to hang our consulting hats on, but it's a good starting point.

Several years ago, Mossback Fish Habitat, a pioneering company from northwestern Arkansas that's taken the lead in the industry, teamed with researchers from South Dakota State University to study a 125-acre lake in east Texas. The study lake, built in 1952, had minimal natural habitat left. There was some standing timber, long since degraded into stumps, and some cedar brush piles that had disappeared within five or six years of being added.

The goal was to determine how much habitat was needed to influence productivity. A bathymetric map was used to determine where to place some well-designed "fish cities." The team also had several years of fish data as a starting point. They had relative weights, percentage size distribution, and data from another study where as many as 40 large bass were surgically implanted with radio tags. Their movements were studied for a year and a half. Researchers also collected data from stomach contents to see what the fish population ate. Combining this data, they hoped to draw some conclusions and publish a scientific paper, which they did.

While there was limited existing habitat in the lake, mainly limited to the confluence of creeks underwater in 8-10 feet of depth, there wasn't a lot of permanent habitat. There were areas where American lotus grew in water up to six feet deep and a few flat, shallow, muddy spots where foraging gizzard shad seemed to attract bigger bass occasionally. Still, most fish seemed to live a random existence. Nomads, so to speak.

In this study, Largemouth bass behavior shifted with added habitat.

The newly added structures, made of plastic, attracted bass. Researchers presumed the habitat attracted bass primarily because the large surface area of these fish cities attracted measurable amounts of forage fish, especially bluegills. That certainly makes sense. I've electrofished across enough of these manmade structures in private waters and collected plenty of bluegills in their confines. Bass tend to linger around the edges, while sunfish are congregated throughout. Although edge cover is significant for bass, density is essential for baitfish, especially bluegills.

For years, anglers have known the value of adding cover and structure to attract fish. Ask any crappie fisherman how they attract their favorite savory fish each spring.

But how much is enough to influence productivity? According to this study, researchers began to see a difference in fish growth rates and relative weights once the lake had around 13% added fish-attraction structures. Fish cities, if you will. The premise? More energy is ingested with less effort. Simple as that. Attract more baitfish, attract more bass. Protect baitfish, raise more mass, and grow more bass.

That's an equation all of us can understand.

Back to the sticker shock part of this equation.

Use this visual...in these studies, a fish city covered 70 feet wide, 70 feet long, five-feet deep to ten feet deep along a sloped shoreline in water from 7-15 feet deep. If we were to reproduce that density, it would take about 300 six-foot cedar trees. Think chainsaws, a pontoon boat, pallets of concrete blocks, wire, and way more help than most can muster.

Each one of those fish cities in today's inflated dollars adds up to $10,000.

Therein lies that sticker-shock thingy.

Those folks studying this project later revised their ideas. Fish cities didn't need to cover that dense an area. Big bass didn't frequent them nearly as well as projected. That's because big bass prefer edge cover. Instead of a square, think more of a meandering, serpentine design—maybe lots of mass with way more edges. Still have the density for forage fish, with considerably more edge cover for bass to linger and await their morsels.

For most of us, that means covering more like 2,500-3,000 square feet of area per fish city at a cost between $3,000-4,500 per unit, depending on how far apart placement is.

While that still seems pricey, look at it long-term. Long, long term...as in "permanent." Once you add that artificial stuff, it will be there forever. So even three or four of these units, custom-designed for your 2-3-acre fishing hole, will influence catch rates for years—fish like them.

The scientific study determined that a lake with 13% habitat coverage positively influences fish production. These same researchers are about to conclude that 22-25% habitat coverage is at the top of the bell curve for productivity, at least in Largemouth bass/ bluegill fisheries.

So, what do you buy?

Today's marketplace continues to evolve. Mossback has been the leader, with a significant foothold.

There are other companies as well. American Fish Tree has advertised on these pages and has essential products with different merits and marketing plans. Another company, Fishhiding, developed products using factory seconds from a siding company to recycle, manufacture and sell their unique fish attraction items. Each of these companies has patents and claims how well the products work and how to use them. Each continues to create new products as science reveals what works best.

Can you build your stuff? Sure, people do it all the time. First, however, you must decide how much time, effort, and dollars you want to spend to gain value for your pond.

New to this niche in the marketplace is Texas Hunter Products. Well known for their hunting blinds, wildlife, and fish feeders, Texas Hunter launched their series of fish habitat products this spring.

Texas Hunter spent two years researching how best to enter the marketplace. They met with Auburn University's engineering department for the initial design. They wanted easy assembly, no tools, easy shipping, and attractive fish. They came up with 168 initial designs and sought opinions from the university's fisheries department. They sought feedback from professional lake managers across the country as well. They wanted something to create shade, something for the conservation of baitfish, and something for spawning, with an array of products to bring a more holistic approach to fish habitat. Their goal was to attract fish, enhance fishing and provide habitat to improve the fishery, bundled with conservation, especially to have permanent materials that are safe for the water. Another goal was to create a complete meal deal so bass don't have to expend much energy to influence growth rates. They created devices that mimic lily pads, provide bases for sunfish spawning, and pyramid-looking devices for tiny fish to navigate for protection. They even developed thin, wispy products that mimic natural grasses like Vallisneria.

Industry leaders are seeing the need and figuring out how to provide what nature wears out. And we can benefit from that once we understand that up-front dollars extrapolate into long-term benefits.

That is, if we can divide that upfront cost by years, that will exceed us.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine