Every one of us doesn't know what we don't know. Because of that little limiting factor of life knowledge and experience of whatever endeavors loom, we often pay the "Dumb Tax." I'd like to take credit for that little epithet, but I must give credit where credit is due. Freeman Sawyer, owner of Heroes Ranch in east Texas, said that to me a few years ago.

It resonated.

I can't tell you how often I've sat around a campfire or in the passenger's seat of someone's side-by-side and heard the landowner say, "I wish I'd done this differently."

That's a common phrase.

We don't know what we don't know. Because of that, landowners pay extra. That's the "Dumb Tax', affectionately speaking. Debbie and I just paid some dumb tax ourselves. Our lesson was expensive, but not compared to some I've seen. Ours? Just because he drives a truck, has a ladder, and wears white pants doesn't mean he's a painter.

There's a new landowner I'm working with now whose budget was overshot by close to 50% because he didn't take enough core samples where his dam was about to be built. They cost $500 each for the Geotech company to drill holes, take the dirt to the lab, and analyze plasticity. They had a $1,500 minimum charge to come out and drill. That's what he did...three holes. Had he done ten holes about 30-50 feet apart all along the proposed dam site, they would have found a layer of gravel six feet deep with a constant flow of water. By not spending another $3,500 in due diligence, it costs close to $30,000 to dig the core trench deeper and wider. That little gravel vein turned out to be an ancient creek channel long since buried with silt and topsoil as floods came and the creek shifted directions over eons.

Because of that underground fact, the contractor had no choice but to figure out how to divert the water to a sump, set up a pump, and send the water down the creek out of their way. Then, they had to dig out the gravel and go down an extra six feet to get to solid material for a foundation for the dam. I'm not saying he could have built this dam for less money, but our landowner was committed by the time his earthmover figured out what was buried beneath them. He might have gone through a different thought process had he known...had he spent the 'extra on the Geotech due diligence before any dirt was disturbed. He could have made a more intelligent decision.

Then there was the central Texas lake a man built himself. He rented a bulldozer and a sheepsfoot roller to pack the clay lifts. He knew enough to build a proper core trench and how to compact the clay as he built the dam. There was a big, beautiful pecan tree just inside where the backside toe of the dam would sit. He and his wife discussed how neat it would be to carve out a picnic area around that tree. The dam would protect them from winds. The tree offered shade. It was almost like they designed a little grotto sans the cave effect. It was a c-shaped indention, basically into the dam. That little design altered the backside slope of the dam, and the tree was so tall that he decided to make the crown of the dam a couple of feet narrower there. The rub came because several lifts of clay were added where the compactor couldn't safely navigate around the tree for risk of falling over. Fast forward a few years. They were enjoying that picnic area. The lake was full and growing some fish; they were having a blast with the whole thing.

He noticed a low spot in the dam adjacent to the tree. He figured out those layers were allowing a small amount of water to percolate through. They had not been compacted well enough. The dam settled. He had a low spot and a seep. There wasn't enough water leaking to influence the lake. About 15 years after the dam, the new owner wanted me to help him grow some big bass. He gave me the backstory of the dam and showed me the leak and the big pecan tree. The leak was minimal; it might fill up a 5-gallon bucket every three or four minutes, so I didn't think much of it. At the far end was the spillway, all rock. It was layered limestone in the hillside. The layers stepped down so the water rolled down when it rained, and he had a beautiful waterfall. About five years into the new guy's ownership, he was watching water roll over the spillway right after a springtime rain. He saw a bunch of baby bluegills leaving his lake and headed downstream. That bothered him enough to call me and ask if he should put a short chicken wire fence across his spillway to keep the fish from leaving. I gave him my opinion...don't do it. Those bluegills are so resilient that they'll keep spawning in his lake and make up for those lost. Chicken wire mesh wouldn't stop a little fish.

About nine months later, I got a call from him.

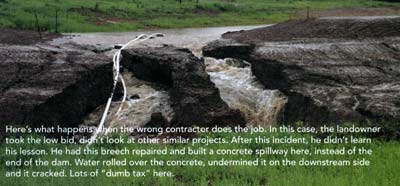

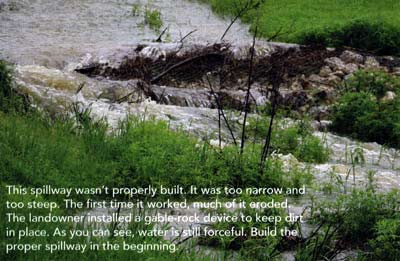

His dam had blown out. He put up that 18" tall chicken wire fence across his spillway. The area had gotten one of those hundred-year floods that seem to occur every 8-10 years. Nine inches of torrential rain poured down the watershed over an 8-hour span and into his lake. His spillway fence was clogged with debris, and the water rose too much, topping the dam at that low spot. That roaring water chewed the backside slope within minutes, eating the dirt away. It built momentum, and within two hours, the dam failed. There was a gaping hole over 50 feet wide at the top, tapering down to three or four feet wide at the bottom, what used to be natural ground level. The big pecan tree was toppled, a loafing barn was pushed over, and a county road was washed away.

Then there was the guy who bought a beautiful property with a lovely lake. He built a cabin a few feet from the water's edge. The foundation was poured, and the framing was up. A hurricane was looming off the coast, with two weather models having it roll right over his property. His builder shot the elevation for the foundation based on the primary spillway, a 24-inch overflow pipe. He'd set the foundation one vertical foot above the overflow pipe. The landowner called me, worried about impending rains from the hurricane. His question was about how big flow rates would affect water quality. He'd recently limed his lake. I headed over to his place with my water chemistry test kit. That was the first time I saw his cabin site. I asked him about the elevation of the foundation. He explained it. I looked across the lake and tried to compare the emergency spillway to the primary overflow pipe. It sure looked more than a vertical foot above that primary pipe. The hurricane was hours away from landfall, and prognosticators still weren't sure of its path. There was an earthmover on site, clearing some areas for food plots for wildlife and clearing out an old cross fence. We headed over, and I asked if he had a transit with him. Sure enough, he did. He had a laser level. We set it up and confirmed that the foundation was one foot above the overflow pipe. But the emergency spillway was six inches higher than that. That meant he'd have 8-12 inches of water in his cabin if the emergency spillway released two to six inches of water. He called the builder on that Sunday, had him take a look, and helped him decide what to do. Since the framing was completed, they discussed it and decided to move the cabin away from the lake and pour a new foundation 18 inches higher than the emergency spillway. The builder paid the dumb tax, and the landowner got a concrete patio next to his lake.

Then, there was the lady who bought a cabin not far from a public lake. She wanted a pond next to the cabin so she could sit outside and drink coffee each morning and see water. She didn't care about having fish, aquatic plants, or any of that. She just wanted to see water from her back porch. After carefully explaining that to the earthmover, she took a two-week vacation. When she got back, not only was the pond finished, it was half full of muddy water from a recent rain. She called me, totally upset. I headed over there and quickly saw why. The dirt guy built a berm right in the line of sight. She could not see the water, even when the pond was full. She wanted me to call the guy...a local guy I'd known because our kids grew up together. She didn't want to call him, something about not wanting to deal with confrontation. He had just finished lunch and said he'd head over.

I was standing on top of the levee of this 1/3-acre pond and figured out what he'd done. He needed a place to put dirt to get the depth needed for the pond. If he pushed it south, he'd interfere with the watershed, and water would flow around the pond. If he pushed it west, it would fall onto the neighbor. He put the dirt where it logically belonged. He explained that he couldn't get her on the phone because she was out of the country, so he did what dirt guys do. She wanted what she wanted and paid the freight for dump trucks to haul off the excess dirt.

I'll always remember one other landowner who built a lake. Three acres of the ten-acre site was way too shallow...less than three feet deep and flattish. He was advised to deepen those areas by building peninsulas or pushing some dirt out of the pond along that area. He'd already spent about as much as he intended and wanted to be finished. His dirt guy didn't know any different, and the landowner didn't understand the consequences. For the next five years, he paid $5-6,000 for herbicides. His pond management company suggested he drain five feet of water off and deepen that area. It cost him $6,000 for dirt work. Had he done that five years earlier, he'd be ahead. Dumb tax...he didn't know what he didn't know.

How do you keep from paying the dumb tax? Either hire people who understand what you want and represent you, immerse yourself in the topic, learn all you can...or both. That doesn't mean you won't pay more than you should, but the more you learn about any project before you do it, the better your outcome will be.

When I was 19, my car's air conditioner compressor froze. The bearings started screaming and locked up, and the belt burned off. There was no University of Google or YouTube videos we could watch to learn how to do things. I took it to a mechanic's shop—$125 to fix it. No thanks. I didn't have that much spare money in my pocket. I headed to the auto parts store, bought the bearings, and headed home. I raised the hood and went to work. I couldn't get the clutch wheel off (or whatever it's called). I returned to the auto parts store and bought a wheel puller and an O-ring tool to get that little jewel out. I was out about $75 by then. I popped that O-ring plier's-looking tool into place, squeezed it, and the dang thang shot straight at me, hissing like a cornered bobcat. Instantly, I was covered with oil, freon, and whatever else lives in a compressor—dumb tax. $180 later, the air conditioner worked. At least I could take the wheel puller back and get a refund. I made up my mind that day that this soon-to-be-fish guy would not work on any more cars.

Seek good counsel, and immerse yourself as much as possible before spending the money. Look at similar projects. Don't be afraid to study other examples and learn from other people's mistakes. Don't ask a fish guy how to lay bricks or ask the plumber how many fish to stock. Find the right people to teach, inform, consult, and educate you about that project. Then, pull the trigger. There are still no guarantees you won't pay more than you should, but you certainly should be able to pay less dumb tax.

We should have asked the guy with the pickup, ladder, and white pants to show us a portfolio of his work. When he pulled cabinet doors and sprayed them out in our yard, didn't sand before the second coat, and painted the still-attached hinges, we should have known...but we didn't know what we didn't know.

We paid the dumb tax.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine