Where I live in Mississippi, ponds rarely have ice cover. Some years we may even not see a snowflake all winter and can wear shorts in January. But every few years, we get a deep, bone-chilling freeze. Temperatures may dip into the single digits and stay there for days. When this happens, most tranquil water bodies freeze over.

The ice may persist for several weeks. It is almost never thick enough for skating or ice fishing, so it is usually best just to stay away from the pond while it is frozen. For us southerners who are ill-prepared for this Arctic weather, the question often turns to, "Do you think my fish are okay?"

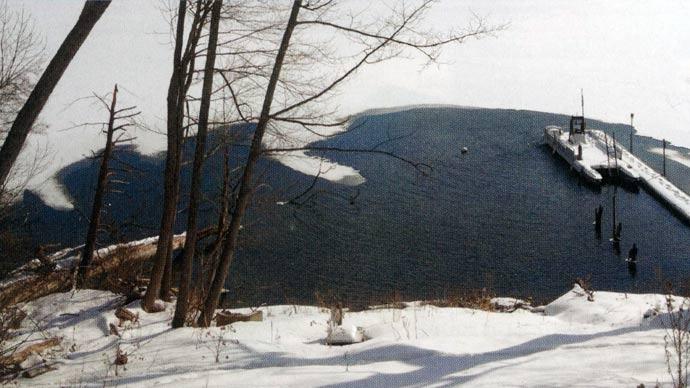

If your pond paradise is further north, you probably are less worried when things get a little frigid. In fact, if you are far enough north, your pond may spend as much time frozen as it does in the ice-free state. When winter is at its worst, some folks might prefer to curl up by the fireplace and stay inside, while others who live where the ice is thick enough might go drill a hole in the pond and keep fishing.

Regardless of whether you are an inside cat or an outside cat during cold weather, have you ever wondered what is really going on under the ice?

Under most circumstances, the fish are just fine. Species with distributions that include more northern portions of the country evolved under these conditions and persisted through the last ice age some 10,000 years ago. For them, this is a perfectly normal part of their lives.

The reason fish can survive through a deep, extended freeze is based on the properties of water. Water is densest when it is about 39 degrees and becomes less dense at increasing and decreasing temperatures. During warmer months, the pond is warmest at the surface and temperature decreases with depth. In the fall the surface cools and the water becomes denser than the layers beneath. It sinks and mixes the pond.

When the pond reaches 39 degrees throughout, the surface of the pond continues to cool. Colder water is less dense and stays at the surface, allowing surface layers to cool even faster. When surface waters reach 32 degrees, ice forms. Ice is only about 90% as dense as liquid water, so ice always freezes on the surface - never from the bottom up. As ice covers the pond surface, it insulates the warmer waters below. Ponds and lakes never freeze solid unless they are in extremely cold climates or very shallow.

Most pond fish species are well adapted to winter weather and survive just fine under the ice. But there are exceptions. Florida Largemouth bass, a favorite with many pond owners, are less tolerant of cold water than the northern Largemouth bass. Under extremely cold conditions, under-ice mortality can occur. This is rare in southern ponds but would be increasingly likely the further north you go.

Threadfin shad, a popular prey species in southern ponds, are very cold sensitive and will die under ice unless they can find a thermal refuge, like a warm spring. This species may die in most ponds with prolonged ice cover and thus requiring restocking the following spring. This can be an issue even in southern ponds.

With an ice barrier between the air and the water, oxygen can no longer diffuse into the water. If ice remains clear and sunlight can penetrate, plankton and plants in the water will continue their natural processes of using carbon dioxide and sunlight to make food, which gives off oxygen as a byproduct. This will keep oxygen levels adequate to support fish.

However, when the ice gets too thick or is covered in a blanket of snow, photosynthesis cannot continue. Respiration does continue, however, as all living things from bacteria to fish use oxygen and release carbon dioxide during metabolism. Even plants do this. They are always respiring, but during the day with enough sunlight, they produce more oxygen than they use, and use more carbon dioxide than they produce. If the plants are deprived of sunlight too long, they may die and decompose, further reducing dissolved oxygen.

Luckily, the cold temperatures slow down biological processes. That means bacteria, plants, and animals are using less oxygen. Also, cold water holds much more oxygen than it would at summer temperatures. Thus, most ponds can maintain adequate oxygen for extended periods without photosynthesis or diffusion. However, more productive ponds (those that are rich in nutrients or with abundant plant growth) will run out of oxygen sooner, as will shallow ponds. If ice and snow cover persist for long enough, winterkill can occur.

Aeration can be used to minimize the risk of winterkill. Ponds that have aerators continuously moving the water may not freeze over or will keep areas near aeration ice-free. However, the mixing of the water during the coldest parts of the year may allow the pond to get colder throughout the water column than it would with a protective layer of ice. So instead of a bottom refuge near 39-degrees, fish might experience colder temperatures. For some species, like trout, walleye, or pike, this is no issue. For other species, like largemouth bass, this could be problematic. One study reported that largemouth bass lose equilibrium at 37 degrees, suggested that the insulation provided by ice is important for this species to survive the winter.

For subsurface aerators, like destratification systems, you can allow a layer of ice to form and insulate the pond before activating the aerator. After several weeks of ice cover, aeration can be initiated under the ice to prevent winterkill. This may also mix the layers and cool refugia but should not reach temperatures as cold as continuous aeration. However, it is also possible that heat produced by the aerator's compressor or motor could help offset this cooling. Make sure to drill a hole for the air to escape.

When using surface aeration, do not walk or skate on ice that forms outside of the aeration zone as it is likely unsafe. Similarly, do not skate or ice fish on ponds with subsurface aeration unless you are certain the ice is sufficiently thick and air pockets are not present under the ice.

Another concern when cold weather approaches is property damage due to freezing water. Water expands about 9% when it freezes. Damages can occur if this expansion occurs inside a rigid structure. It is a good idea to eliminate water in feeders or other items before the cold snap arrives to prevent damage. Get boats out of the water and store them dry. Docks are also susceptible to damage.

Cold snaps can have some benefits. Many of the plant species that cause spring and summertime problems in ponds do not like drying and freezing. You can draw down the water level during the winter to expose plants on the shoreline, making them susceptible to drying and freezing. However, make sure you properly identify the plant species and discuss this option with an expert, because some species of aquatic plants may spread to new areas during the drawdown. Dewatering around shallow docks can help prevent ice damage.

Winter is also when many fish species bulk up and put their energy into developing eggs. There is a reason that the biggest fish are caught in the late-winter and early-spring-that's when they are gravid, or laden with eggs. Females are often 5 to 10% heavier due to the eggs they carry, and some may be even heavier. These eggs are produced during winter when body growth slows.

There is even some evidence from more tropical climates (where there is no winter) that suggests winter acts as an important reset period for largemouth bass. Without this reset, the species spawns frequently and burns itself out in a few years. Few fish live more than 3-5 years under these conditions. It is no coincidence that the oldest known largemouth bass was from a northern lake just northwest of Albany, New York at a latitude of 42.8 degrees North. Only 6.78 pounds, this bass was 23 years old. She may have grown slowly in the cold water, but she grew for a long time!

My bass in Mississippi may not live as long, but I will take the much faster growth and larger maximum size. And I don't have to worry about winterkill under ice. Yet, there are times in the dead of winter when there's nearly an inch of ice on the pond when I wonder, "Should I buy an ice auger?"

Dr. Wes Neal, Extension Professor at Mississippi State, serves as State Extension Fisheries Specialist, passionate about educating the public on small lake and pond management. He is an avid researcher on topics from farm pond management to sport fish genetics. Wes is the lead editor of Small Impoundment Management in North America, the only textbook on the subject. He loves to hunt and fish, wes.neal@msstate.edu.

Reprinted with permission from Pond Boss Magazine